In the opening scene of Sugarcane, a radio broadcast features a woman discussing the discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves at a Residential School in Kamloops in 2021. She mentions how this discovery “reopened old wounds for Indigenous families torn apart.”

However, for those directly affected by this system, these wounds were never fully healed. As more details emerge about what happened in these schools, it’s clear that Residential Schools are a painful chapter in Canada’s history.

This topic is rarely discussed, leaving many survivors to face their pain alone. Yet, Julian Brave NoiseCat and Emily Kassie’s documentary Sugarcane brings this conversation to the forefront.

With compelling visual storytelling and a focus on harsh truths, NoiseCat and Kassie create a gripping documentary that honors survivors and highlights the long-term effects of generational trauma.

The film tells the stories of Residential School survivors in their own words and demands accountability for the abuse these institutions inflicted on children for over a century, while many of these wrongs remain unpunished.

What Is Sugarcane About?

Sugarcane examines St. Joseph’s Mission School, located near the Williams Lake First Nation in British Columbia, known as Sugarcane. The documentary starts with somber images and title cards, explaining that in 1894, the Canadian government decided Indigenous Peoples needed to be assimilated.

Through survivor stories, we learn how children were taken from their homes and sent to Residential Schools, where they were given numbers instead of names, forced to learn a new language, and violently punished for disobedience.

These children faced corporal punishment and sexual abuse from priests, with many girls becoming pregnant, and numerous children either dying or disappearing. The trauma from these schools affects many survivors and their descendants, with some even taking their own lives due to the unbearable pain.

In Sugarcane, investigators Charlene Belleau and Whitney Spearing lead the probe into St. Joseph’s Mission. Chief Willie Sellars handles hateful emails and talks to well-meaning politicians, while Chief Rick Gilbert travels to the Vatican to hear an apology from Pope Francis.

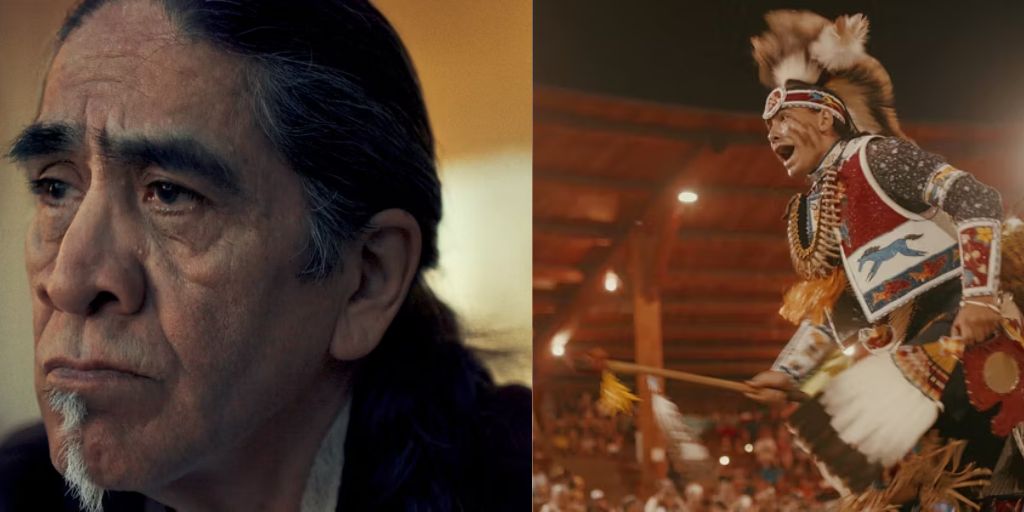

A central part of the film is co-director Julian Brave NoiseCat, who explores his complex relationship with his father, Ed Archie NoiseCat, who is trying to understand his own history after being born at St. Joseph’s. The documentary focuses on accountability, showing how current political figures and past school employees avoid taking responsibility for the harm caused.

The cinematography in Sugarcane, by Christopher LaMarca and Emily Kassie, is striking. While the beauty of British Columbia’s scenery is showcased, the filmmakers use contrast effectively. Scenes of colorful celebrations at the Kamloopa Powwow are mixed with shots of barren forests and graveyards.

A shot of a cozy fireplace early in the film hints at the later revelation of past horrors. Sugarcane is a stark reminder that those haunted by the trauma inflicted by the Canadian government carry that pain with them. The film mixes joy and sadness, with reminders of the graveyards never far away.

Canadian nationalism appears in the film, with Tim Horton’s cups and an inflatable tube man showing the contrast between pride and the reality of living on stolen land.

Instead of using talking heads, Sugarcane reveals information as the investigation unfolds. We sit with survivors in their grief and feel the pain of the investigators as they examine documents of abuse. The camera serves as a patient observer, allowing the subjects time to express their stories.

The film avoids distracting music or camerawork, making the audience witness the pain directly. The creative choices by Kassie and NoiseCat make the story even more powerful, with every detail feeling intentional.

While Sugarcane does not shy away from showing the ongoing pain and trauma faced by Indigenous communities due to Residential Schools, it also highlights that survivors are much more than victims.

The film honors their grief but also includes moments of joy, such as Julian and his father singing in the car, Ed creating beautiful sculptures, and Chief Richard Gilbert playing music. Despite the tragedy, their lives are full of resilience and culture, and Sugarcane celebrates both aspects.

Sugarcane is a crucial film for all Canadians. It reminds us that history is not just something to avoid repeating but is a part of our present pain. As Canada works towards reconciliation, Sugarcane should be essential viewing while the truth about Residential Schools continues to be uncovered.

The film features Indigenous history as told by Indigenous people, highlighting that while the last Residential School closed in the late nineties, there is still much work needed. The interactions with political and religious leaders in the film make it clear that the steps toward reconciliation are important but insufficient.