Colonial Massachusetts saw a hysteria that made people run wild on the streets with torches and in mobs. As it took place, in the years 1692 and 1693, men and women were accused of practicing the dark arts, which led to their death. While no one would happily oblige to get their neck broken, the Salem Witch Trials made sure that over 200 residents were dragged to trial accused of consorting with the Devil while 30 were charged guilty, and 20 of them were blatantly executed, often with little to no evidence. Many passed on in their dungeon cells, and still, others were imperiled to extreme agony.

The belief in demons has been rampant amongst Judeo-Christian religions since their conception. Humans who indulged in these powers of the dark were referred to as witches and deemed to have extraordinary abilities to torment others. This fear of those subject to malpractices spread rapidly amongst the Europeans during the 1300s and reached the rest of the world. Arrests of these “criminals” were rebounding in Salem and all the towns and villages around it. Grand juries were being called in at the Court of Oyer and Terminer, followed by the Superior Court of Judicature. A “witch hunt” began devouring everyone it considered to be vulnerable in its wake.

Also Read: The Chernobyl Mothman: The Nuclear Incident

How It Came To Be?

An amalgamation of different happenings had unfortunately led to the trials, which for the most part, had nothing to do with actual witchcraft. During the late 17th century, under the conjoined rulership of William III and Mary II, a war was started against the French in the American colonies. In 1689, King William’s War ravaged Quebec, Nova Scotia, and upstate New York.

The war forced refugees into Essex and drove them to the then region of Salem in Massachusetts Bay Colony. The sudden increase in population proved detrimental to the region’s resources. The farming families saw their feuds of wealth fueled by the unnatural lack of provisions, smallpox endemic, and threats from the warring tribes. All feelings of rage and unpleasantry were directed towards Reverend Samuel Parris, appointed in the light of the war.

He was accused of being stringent and greedy, and soon the colonial Puritans began to believe that the Devil was at work in the unrest. The issue was aggravated when a suitable discourse was found. The Minister’s daughter, 9-year-old Elizabeth, and her elder cousin, 11-year-old Abigail Williams, were having seizures. The girls resorted to strange angry behaviors, like imminent tantrums, laying twisted on their beds, and speaking in odd tongues. Their physician claimed the nature of the distress was occult. Soon another 11-year-old called Ann Putnam showed similar symptoms.

Also Read: Dungarvon Whooper: The Legend of A Unfortunate Cook

The Beginning Of The Salem Witch Trials

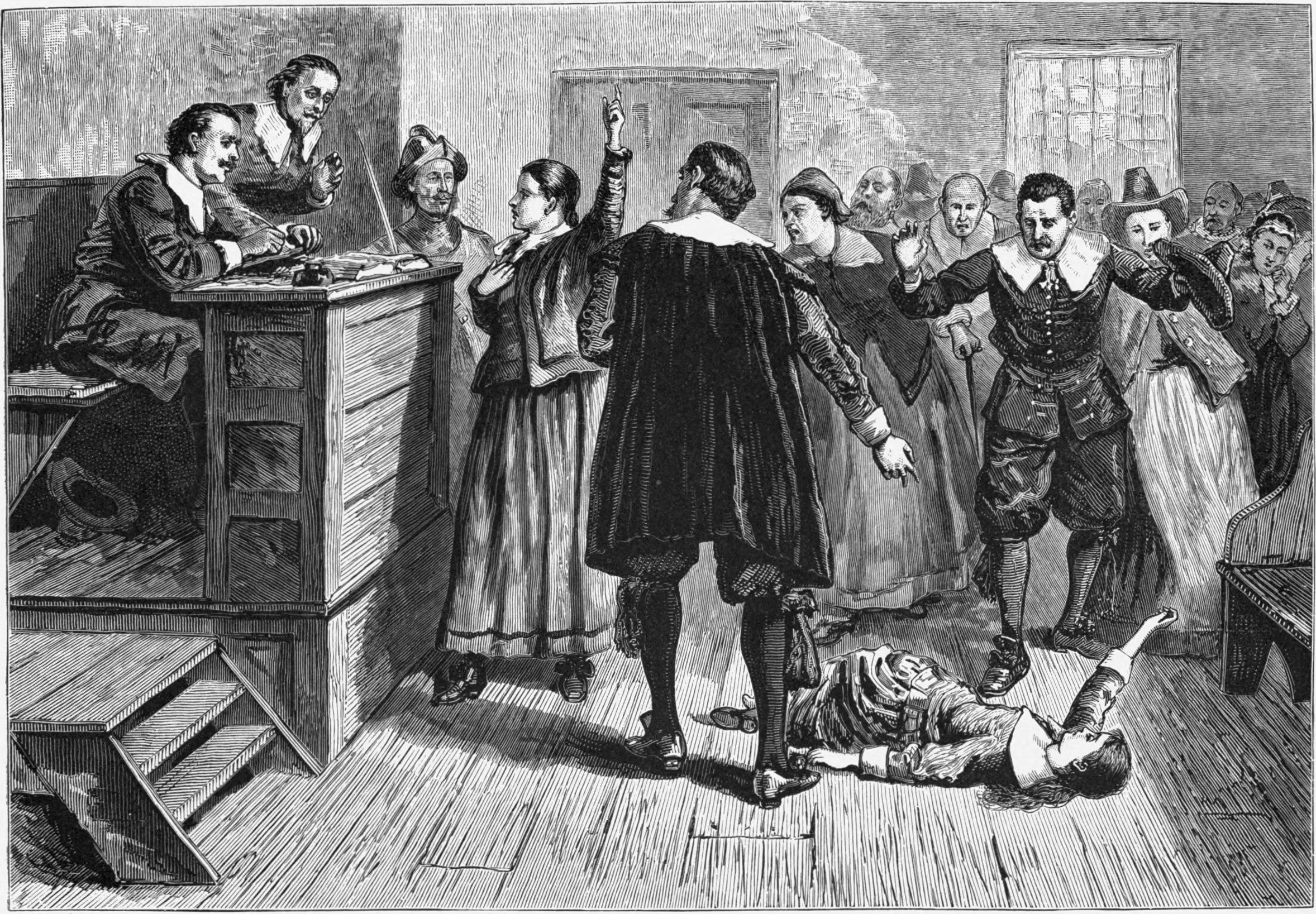

When the local magistrates, John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin, pressurized the girls for the names of their tormentors on the 29th of February 1692, the girls are said to have given the names of a Caribbean slave of the Parris called Tituba, a beggar called Sarah Good and a poor elderly lady called Sarah Osborne. When the women were brought to court on the 1st of March 1692, the two Sarah claimed innocence. Tituba, not so.

Perhaps under the weight of her enslavement, she confessed to consorting with the devil and having signed his “book”. She explained with elaborate detail the tales of yellow birds, red cats, and black dogs. The three women were thrown into prison. Soon other women were being blamed for the same. Sarah Good’s infant daughter, a 4-year-old Dorothy, was accused of witchcraft, and so was Martha Corey, a devoted church-goer. Suspicion grew in the villages as people pointed fingers at each other.

By the time Deputy Governor Thomas Danforth paid visits to the hearings, the paranoia spread like wildfire in a dry thicket. The Puritans began to quote verses from the Bible. Inspired by Joseph Glanvill’s Against Modern Sadducism, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live”, they yelled Exodus 22:18 out, and Boston minister Cotton Mather who believed witchcraft was adamant, was not convinced of the evidence being produced at the hearings.

Unfair Renderings

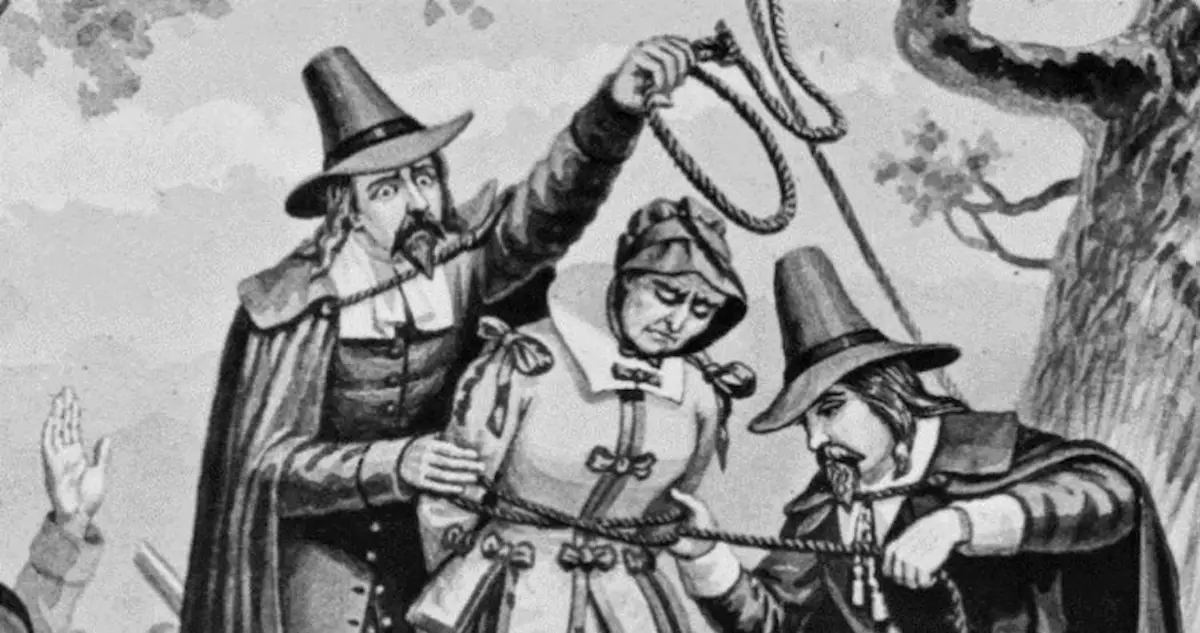

A special court was set up for the witch trials of the counties Essex, Middlesex, and Suffolk by Governor William Phipps on the 27th of May, 1692. Bridget Bishop was brought in. Accused of witchcraft, which was more than her usual hobby of gossiping, she denied it. The denial was not received, and by the 10th of June, she hung at the Gallows Hill. Minister Mather was not convinced of the authenticity of these trials and wrote a letter to disallow spectral evidence in the court.

The advice was never taken under the pretense of several causes, and five more deaths were executed, increasing each following month. Confessions were being coerced, and people were driven mad with torture. His son, Increase, who was then president of Harvard, wrote a similar plea on the 3rd of October, and the Governor, who saw that his wife was being thrust into the mess, dissolved the court by the 29th and replaced it with the Superior Court of Judicature, taking the Mathers advice into account.

Though the fervor had gone down and fewer people were being deemed guilty, the executions did not stop. By the time the witch hunts were over, 19 were condemned to hanging on Gallows Hill, and an elder man of 71 years was pressed to death. Innumerable lives had suffered and defamed.

Rehabilitation

When the light was shed upon their eyes, on the 14th of January 1697, the public and judges ordained a day of fasting to confess their guilt and inaccuracy. The executions were deemed unlawful by 1702, and a Bill for the rehabilitation of the executions was passed in 1711.

A sum of 600 euros was issued as moral compensation to the families of the deceased. A Bill of Rights was demanded in 1787 so that such unlawful proceedings might never happen and everyone should be given the justice that an individual is entitled to under the English common law. Almost three centuries after the violence committed in Salem villages, Massachusetts publicly apologized for the wrongdoings in 1957, and a Proctor’s Ledge Memorial was erected in 2017.

Also Read: Jonathan P. Lovette: The Horrific Incident of the Air Force Sergeant & UFOs