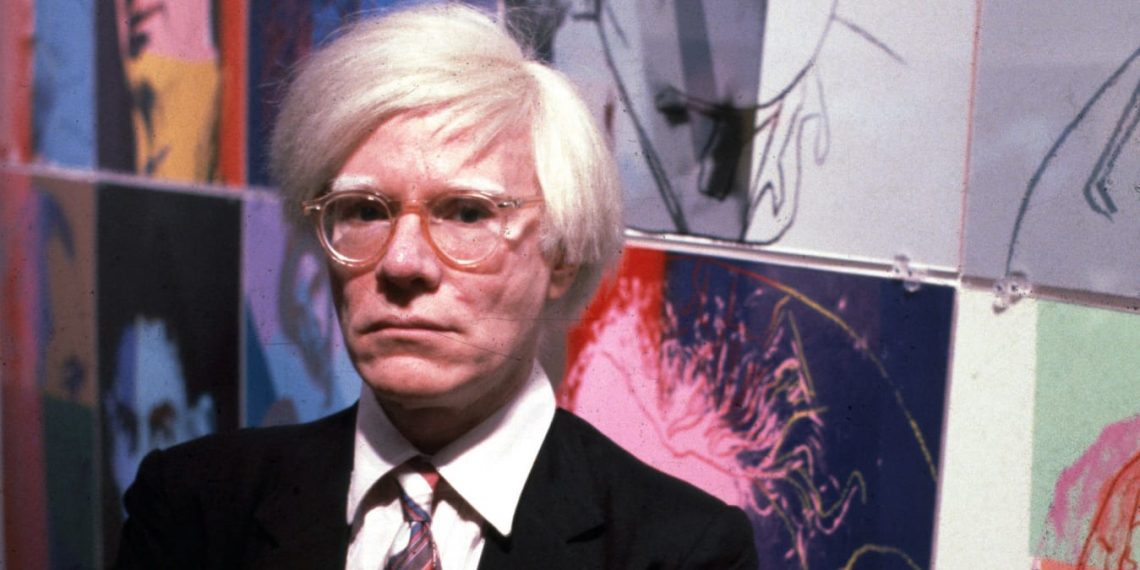

Andy Warhol, an American pop artist, was one of the most well-known figures in the art world throughout the twentieth century. He was a major pop icon who had a significant impact on 1960s advertising and celebrity culture. Although he is best renowned for being the founder of the Pop Art movement, Warhol also dabbled with filmmaking. In the 1960s, Warhol took a sabbatical from painting and began making experimental films after becoming (in)famous for his pop-art depictions of everyday objects such as Campbell’s Soup cans and silkscreens of Marilyn Monroe. Painting, silkscreening, photography, sketching, video, and sculpture were among his many mediums.

In his 60-plus films and about 500 black-and-white screen test portraits, he experimented with the video format, but his avant-garde art films failed to find commercial success. Warhol was fascinated by and gently derided the experimental films of the time, pushing the boundaries of taste. Drugs, sex, and violence remained just outside, and eventually directly within, the frame of already-lengthy movies that were shown at a slower speed.

His works have always shown a dual interest in commercial and avant-garde cinema, and his impact has now spread to both. Now we’ll look at some of Andy Warhol’s controversial and outlandish films, films that revolutionized the way we think about filmmaking.

7. IMITATION OF CHRIST (1967)

Imitation of Christ was shot in January 1967, when Andy Warhol shot sixteen 32-minute reels for the film. The lengthy version was only shown once, in November 1967, before being discontinued. Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey re-released the film in late 1969, condensing it to 105 minutes. This Andy Warhol video is allegedly based on Thomas A. Kempis’ spiritual guide Imitatione Christi. Imitatione Christi is a dramatic comedy about a peculiar yet handsome young man who spends time with the household maid, who reads to him from Imitatione Christi.

Meanwhile, the man’s mother and father squabble in bed about their son, attempting to figure out what’s wrong with him while lamenting their own predicament. Scenes of the son walking around San Francisco’s streets with a hobo are intercut. Pie in the Sky: The Brigid Berlin Story, a 75-minute US documentary on Brigid Berlin’s life made by Vincent Fremont and Shelly Dunn Fremont, includes excerpts from The Imitation of Christ as well as an interview with Taylor Mead.

6. Vinyl (1965)

Because of cooperation with writer Ronald Tavel, Vinyl is more conventional than his other works in that it is a scripted film. It is, however, still experimental, blurring the lines between fake and real violence. As the film begins an apathetic investigation into the dichotomy of torture, Warhol’s aesthetic vision works very well with Burgess’ ideological exposition. It certainly adds to the vast A Clockwork Orange discussion.

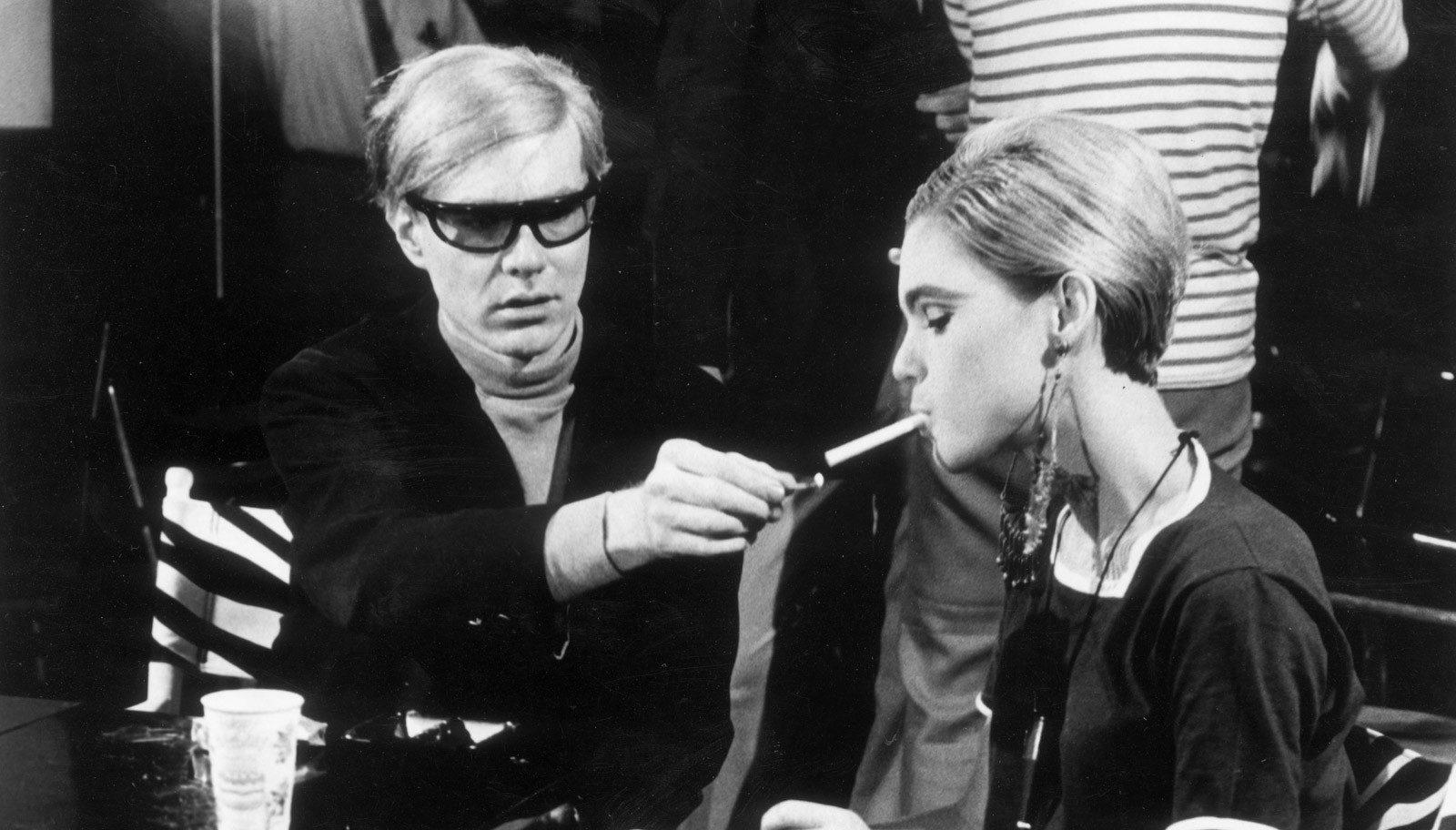

Andy Warhol directed this avant-garde monochrome disturber in his New York City studio, The Factory, as the first adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ novel A Clockwork Orange. It appears to have been shot without rehearsing and is portrayed as a series of unstaged pictures of sadism and suffering carried out by a group of men under the supervision of a gorgeous woman (Edie Sedgwick). It retains an aggressive stance, follows an unorthodox plot, and incorporates many of the characteristics of Warhol’s work, including a concentration on violence and erotica, as well as some very excellent tunes.

5. LUPE (1965)

Warhol’s most recent collaboration with Edie Sedgewick is a near-postmodern look at the life and death of actress Lupe Velez. With pictures of Sedgewick-style activities deleted, it appears to act as much as a study of its major protagonist. With photos of her with her head in the toilet, a reference to reports that Velez died in this manner. It’s never noted that this could be a reference to Sedgewick’s lifestyle, which includes having her own vices and having suffered from bulimia so severe that she was hospitalized for it as a teenager.

A biography that focuses on the star rather than the subject. It’s no surprise that critics like Clement Greenberg saw Warhol as a continuous illustration of everything they despised about postmodernism. We, on the other hand, are huge fans of postmodernism… While I won’t go so far as to declare that A Taste Of Cinema was correct in placing Warhol as the finest avant-garde filmmaker, I will say that A brief look at some of his most memorable events reveals he belongs there.

4. Beauty #2 (1965)

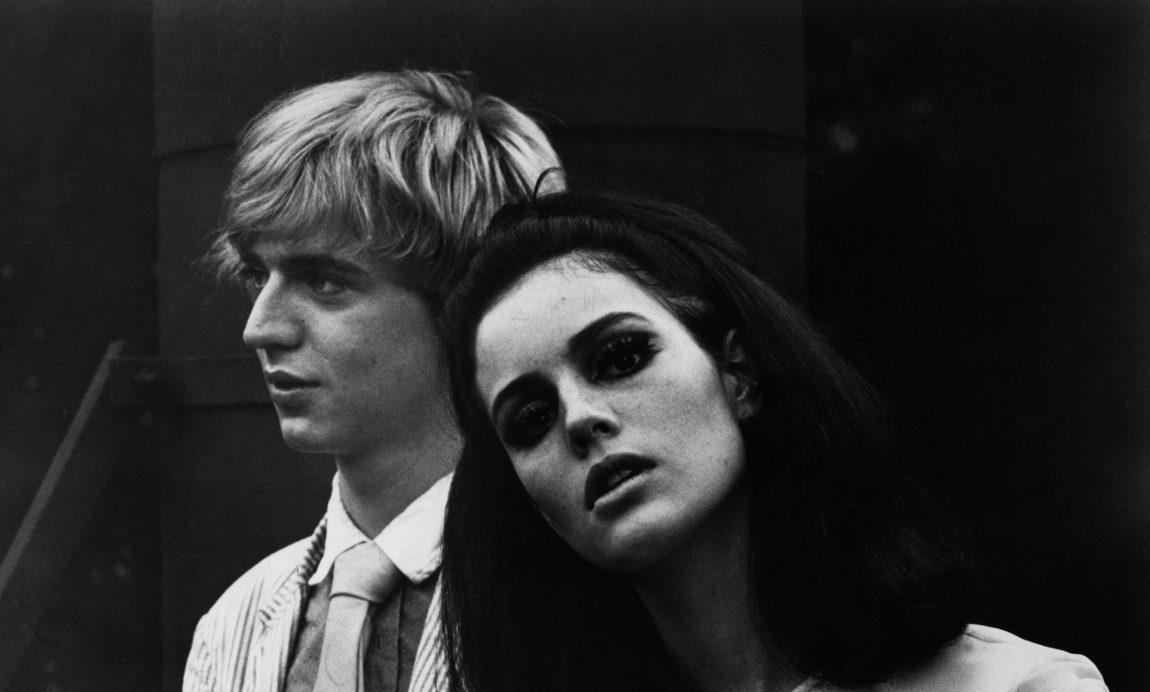

Beauty #2 became avant-garde by teasing the sensuous realm but never entering it, as Warhol did regularly. The film has a fixed point of view that shows Sedgwick and Piserchio lying on a bed. Chuck Wein, the film’s screenwriter, is overheard but not visible. Sedgwick is dressed in a lace bra and pantyhose, while Piserchio is dressed in only jockey shorts. They flirt and light kiss. Wein appears to be harassing and annoying Sedgwick by asking her questions. Piserchio is a bystander who doesn’t interact with Wein in any way.

This film, like practically all of Warhol’s and Morrissey’s, is fascinating. Using the one, static shot signature – and putting Edie Sedgwick in the spotlight. The way the taunting elicits aggression, and the way Sedgwick gradually approaches retraction from the masculine gaze on the side of her boyfriend and us as viewers, transforms her from an objectified piece of beauty to a person behind the guise of her performance.

3. Outer and Inner Space (1965)

Andy Warhol’s first double-screen film, ‘Outer and Inner Space,’ was shot in August 1965 and serves as a transitional piece, as the double-screen format would become highly essential in his later films. Edie Sedgwick sits in front of a television monitor, watching a taped movie of herself in Outer and Inner Space, a 16mm film. The “actual” or “live” Edie Sedgwick is seated on the right side of the frame, while her video image is behind her, and she is speaking with an unseen individual off-screen to our left in the film.

This design has the unusual effect of giving the impression that we are watching Edie converse with her own video image at times. The film is divided into two reels, each of which is 1,200 feet (33 minutes) long, and the videotapes that play within it are each 30 minutes long. With sound on both reels, the two film reels are projected side by side, with reel One on the left and reel Two on the right. So you see four heads rotating between video and film, and occasionally all four heads are talking at the same time.

Also Read: Val Kilmer Best Movies: From Batman Forever To Top Gun

2. Poor Little Rich Girl (1965)

Notably, it was Warhol’s first film to showcase the magnetic Edie Sedgewick, one of cinema’s most renowned muses. Poor Little Rich Girl also explores Pop Art’s favorite juxtapositions of the mundane with the larger, more glitzy world. Early Warhol films like “Sleep” show the collision of Pop Art with the emergence of Cultural Studies and the idea that the mundane could be worthy of artistic investigation. But what happens when someone’s not-so-ordinary daily activities are the focus?

Close-ups of Sedgewick’s daily activities, such as getting coffee and doing make-up in the morning, were a hit with Warhol. The mixed-use of regular filming and out-of-focus footage from a broken reel that had been unintentionally utilized, along with other counter-culture behaviours such as smoking pot, gives the film a strangely moving sense. Many of Warhol’s most memorable films featured Sedgewick’s fatal beauty, but none more so than here.

1. The Chelsea Girls (1966)

Many critics were initially skeptical of this film, which has since become considered as an art-house masterpiece. “Warhol has nothing to say and no technique to tell it with,” stated film critic Roger Ebert after seeing it. This film, which Warhol co-directed with Paul Morrissey, is now regarded as a groundbreaking avant-garde classic. Its split-screen approach has an unmistakable influence on current movies and television.

The two screens in “Chelsea Girls” are split between two projectionists, thus it’s a watered-down version. It might be read as a meditation on life’s two facets or simply an artistic depiction of a super-cool planet occupied by one who works in monochrome and the other in color. Brigid Berlin, Ondine, Nico, and Gerard Malanga are among the “Warhol celebrities” photographed in the famed Chelsea Hotel’s natural setting. Although the avant-garde has had a lot more to say, this could be its “coolest” moment.

Also Read: Brandon Routh’s Best Movies and TV Shows