A two-week-long imitation of a jail milieu served as the setting for the Stanford Prison Experiment (abbreviated as SPE), which sought to determine how contextual variables affected volunteers’ responses and behaviors. College students acted as officers or convicts in a jail simulation as part of the psychological study known as The Jail Experiment.

On the 17th of August of 1971, the prestigious Stanford University hosted the research, which was supported by the American Office of Naval Research. And over two weeks, it was meant to assess the influence of identity, labeling, and societal pressures on conduct. But after a day less than a week, chief researcher Philip G. Zimbardo called an end to the study because inmate abuse had worsened to frightening levels. Today it inspired the 2015 movie called “The Stanford Prison Experiment”.

Volunteers were recruited from the adjacent neighborhood by using a newspaper advertising that paid $15 per day to male college responders interested in participating in the case study of the jail setting. Following psychological examinations, individuals were chosen, and either criminals or prison personnel were assigned to them at random.

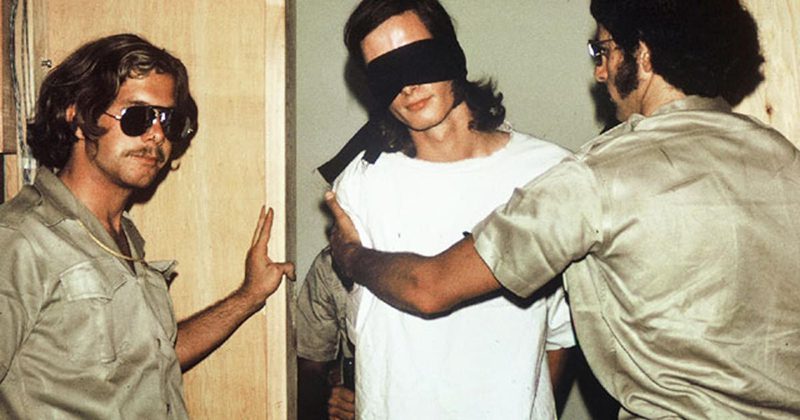

Individuals selected to act as police were equipped in attire tailored to de-individuate them and given instructions to prevent detainees from leaving. The exercise officially began when genuine Palo Alto police grabbed the alleged convicts. During the next five days, the “guards'” mental attack on the captives became increasingly brutal. They had no clue what was going to happen to them.

Also Read: The Horrible Plan of Operation Northwoods

Something Was Not Right

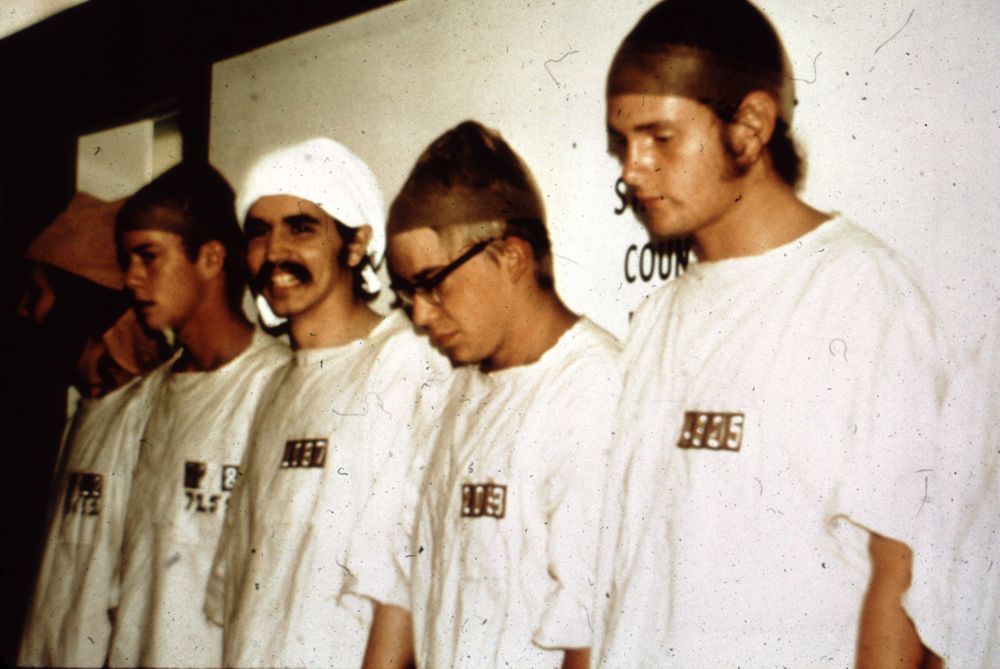

The processes involving every inmate’s entrance were recounted by Zimbardo in a lecture to fellow Stanford colleagues just after the test’s end. Each guy was sanitized, undressed, and inspected before being issued a uniform consisting of a coded garment, which he referred to as a dress which had loose-fitting latex slippers, a headgear fashioned from a lady’s nylon stocking akin to shaved heads, and a hefty fastened cord at the ankle.

Zimbardo noted that although actual male inmates do not wear dresses, it is well documented that they do feel degraded and castrated. We reasoned that by dressing males in a gown without any undergarments, we might swiftly achieve the same results. The guards were outfitted with khaki uniforms, truncheons, whistles, and aviator shades.

The convicts rebelled after just two days. The security officers frequently worked without clear, real-time directives. To control the convicts, they next developed a system of incentives and penalties. A member of the fake officers, Dave Eshelman, claimed to have intentionally built his character as a guard.

Three convicts were freed after just four days because they had suffered so severe trauma. Several of the officers became nasty and oppressive throughout the experiment, and many of the detainees experienced depression and confusion. Zimbardo won’t complete the study in just under a week after it began when Christina Maslach came to assess the circumstances and was shocked.

Also Read: Freddy Krueger Incident: Vietnam’s True Nightmare Mystery Story

The Repercussions And Ramifications

The academics publicized the results in Naval Research Reviews, the IJCP, and the New York Times Editorial before submitting it to American Psychologists and other consensus publications. Zimbardo’s research was disregarded by David Amodio, a clinical psychologist at both New York and Amsterdam Universities, who claimed that the publication of the paper in an ambiguous magazine showed that Zimbardo had failed to persuade other researchers of the dependability and plausibility of his research.

By printing in other publications before a professional peer-reviewed magazine, Zimbardo’s move went against the established pattern of academic distribution. To be released, the work still had to meet the American Psychologist’s extremely stringent criteria, which is the publication that the American Psychological Association officially publishes.

Humanistic concerns about the Stanford Experiment were raised early on. Zimbardo, a specialist, said that he had appeared more like a bailiff at times throughout the probe. He then stated in a statement that the guards’ damaging behavior was prompted by the study’s power structures and external forces. On the other hand, it is said that the old advertising drew totalitarian impulses.

The BBC Prison Study, an investigation that was conducted differently and was the subject of the British Broadcasting Corporation show called The Experiment of 2002, presented the most obvious rebuttal to the Stanford conclusions years later. The BBC’s dummy convicts were more forceful than Zimbardo’s. The Stanford experiment confirmed the results, showing how easily ordinary individuals may become vicious rulers if allowed too much authority. It is claimed that the Stanford Prison Experiment proves that everyone has primordial inclinations that, given the right circumstances, may lead us to become dictators.

Also Read: The Buford Pusser Story: The Sheriff Of Tennessee