China was undergoing massive transformations in the 1980s. The governing Communist Party first permitted international trade and a few private enterprises. The goal of the leader Deng Xiaoping was to increase living standards and the economy.

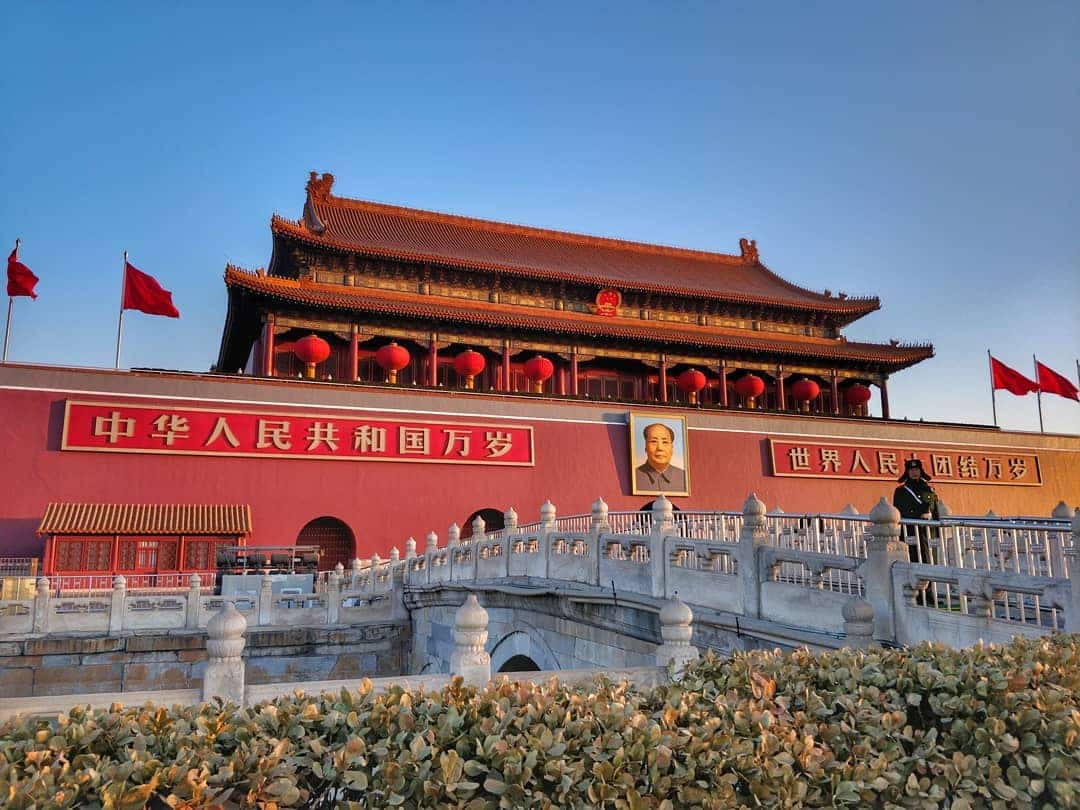

While the change raised aspirations for more transparent politics, corruption nonetheless accompanied it. Hardliners who wanted to preserve strong state control split the Communist Party among those calling for more swift reform and them. Tiananmen Square of Beijing, China, soon became the site of growing student demonstrations in 1989. Documentaries premiered in 1995 called “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” and in 2019 named “Tiananmen” based on this incident.

Scores of student protestors engaged in a hunger strike on May 13 at Tiananmen Square to demand discussions with Communist Party officials. One million protesters, who were there to show their gratitude to the students who were starving and on call for reform, are thought to have taken part in the demonstrations in Beijing.

On May 19, party officials went to the student demonstrations. That nightfall, the protestors broke their fast. Martial law was nonetheless imposed in Beijing the following day to firmly suppress the uprising. Thousands of citizens rallied once more in the weeks after the imposition of martial law, while similar rallies also occurred in other Chinese cities.

Also Read: Josef Mengele: The Nazi Angel Of Death

How It Started

The abrupt death of General Secretary Hu Yaobang from a cardiac arrest on April 15, 1989, sparked a tremendous reaction among students, many of whom thought that his death was connected to his removal from office. Students gathered in great numbers after hearing of Hu’s passing. Posters praising Hu and urging the preservation of his memory were widely distributed on college campuses.

Around the People’s Heroes Monument of the Tiananmen Square area, modest, unplanned assemblies to grieve Hu started on April 15. On April 17, a wider audience gathered for the wreath-laying ritual. Five hundred students from the CUPL arrived at the Great Hall’s eastern entrance by 5 o’clock. Soon with the PKU association’s arrival, numbers grew to over 3,000.

The majority of students had abandoned Xinhua Gate by April 20. Police employed batons to scatter the 200 or so remaining protesters; there were several small altercations. Many students thought that the police had mistreated them, and allegations of police violence swiftly circulated. Youngsters on campuses were upset by the event, those that were not politically engaged enough to participate in the previous demonstrations. Additionally, two handbills criticizing the leadership structure were distributed by a group of Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation employees. By the 21st, 100,000 students were pushing through the Great Hall to see the funeral on the 22nd.

Guo Haifeng, Zhang Zhiyong, Zhou Yougjun, and Wu’erkaixi begged to see Li Peng, the Premier, but the young crowd grew boisterous with no response. By evening there were arsons and destruction all over Xi’an and Changsha. Situations worsened in Wuhan, and Zhao Ziyang, the then General Secretary, called the PSC, AKA the Politburo Standing Committee, to quell the riots. The Premier’s pleas for serious action fell on deaf ears. The police arrested three hundred fifty during these riots. After this, things only escalated, leading to martial law being pronounced.

Also Read: Unit 731: The Atrocities Of Japan During World War II

The Death And Repercussion

The most famous occurrence of this devasting but necessary protest was the Tank man, who became the riots’ icon. By the 3rd and 4th of June, there were multiple accounts of military cars running down citizens. A solitary guy entered Chang’an Avenue at around midday on June 5 while lugging what looked to be two shopping bags in formals.

The driver of a leading government tank first did not try to maneuver past the man who was to be remembered in history by the name “Tank Man,” but rather it came before him at a standstill. The man did not budge. When the tank driver sought to maneuver to the other side, Tank Man leaped into its path.

The Chinese government proceeded to seek out people participating in the protests. After unjust trials where they were accused of committing “counter-revolutionary” crimes, thousands of individuals were arrested, tortured, incarcerated, or put to death.

According to the Chinese government, two hundred civilians and a dozen security officers were alleged to have been killed towards the end of June 1989, although these claims were never corroborated. Various figures have been made, ranging from hundreds to thousands. In 2017, it was discovered that Sir Alan Donald, a former British envoy to China, had stated in an intelligence report that 10,000 people had perished.

The 1989 crackdown and Tiananmen remain officially forbidden subjects in China. There is not a recorded death toll. No public debate is permitted, and attempts to remember what occurred and seek retribution have been violently suppressed to this day.

Also Read: Cambodia Killing Fields: Slaughters By Pol Pot And The Khmer Rouge