On the foot of the Berkshire Hills of Western Massachusetts, there is a long tunnel that has been plagued by stories of misery, pain, paranormal and eerie. It’s nicknamed as the Bloody Pit, a name it well deserves, considering its morbid history of killing hundreds of men who died building it.

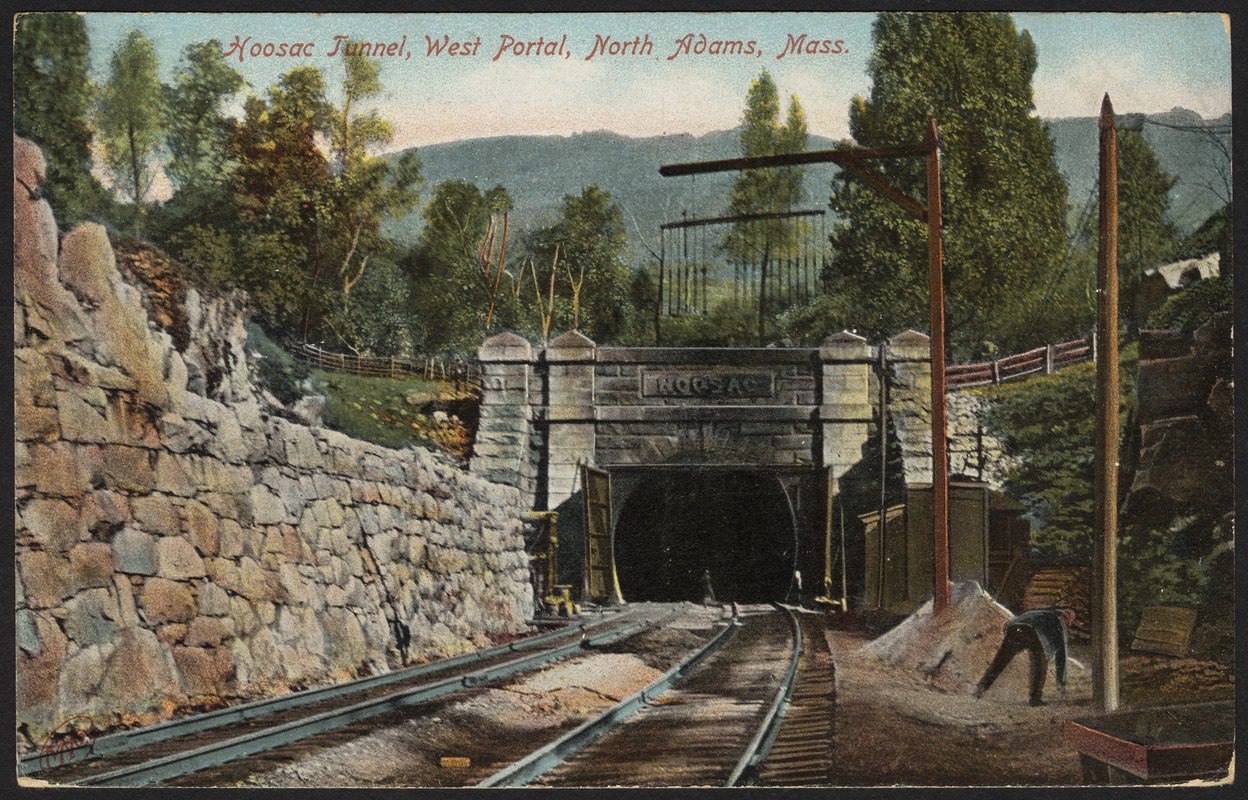

The real name of this monstrous tunnel is Hoosac. It’s a mammoth 5-mile tunnel that carves through the Hoosac mountain range. When it was commissioned, the tunnel was the second largest in the world. According to Mohawk legends, the tunnel actually means forbidden, though many speculate that it’s a part of the folklore.

The recorded meaning of the place is a stony place, an apt name, considering the surroundings. The eerie tale is a good fit for Halloween, and in the safety and comforts of our homes, it’s certainly exciting to discuss the old tale with friends. But in the darkness of the Hoosac woods, the ghostly legends are enough to send a shiver down your spine.

What happened at Hoosac?

The legacy of the Hoosac tunnel was carved with blood, sweat, and tears. It was a mammoth task and unlike anything that was seen so far. The works on the tunnel began in 1851, but the tunnel wouldn’t be completed until 1975. And throughout the twenty-four demanding years, the workers chipped away parts of the unyielding mountain, piece by piece, using pick-axes, shovels, and black powder.

By the time the marvel of engineering was finished, over two hundred men had lost their lives, trying to make the world a better place.” Though many had died from explosions, asphyxiation, and fires, there is one death that looks like a well-planned revenge murder.

Hoosac tunnel introduced the use of explosive nitroglycerin for construction in 1865. However, accidents and fatalities soon arose. Workers Ned Brinkman, Billy Nash, and Ringo Kelley planted a charge of nitro inside one of the deepest parts of the Hoosac tunnel and ran toward a safety bunker on the afternoon of March 20, 1865. Unfortunately, Brinkman and Nash would never make it out alive. Kelley set off the explosives before the two arrived, and the men were buried alive under tons of mountain rock.

However, soon after the incident, Kelley disappeared. He wasn’t seen again until the 30th of March, 1866, almost a year after the tragedy. Kelley’s lifeless body was discovered deep inside the Hoosac tunnel, and an autopsy soon concluded that he was murdered via strangulation.

Though an intensive investigation was carried out, a suspect was never arrested, leaving the case unsolved. But the superstitious workers had their own theories. They believed that Kelley was murdered by the vengeful spirits of Nash and Brinkman. Citing this and the reports that the spirits of the men were sighted inside the tunnel, the workers refused to enter the cursed tunnel, and many even left the project.

Read More: The Californian Dark Watchers: The Native Legend

To put the claims to rest, Paul Travers, a mechanical engineer, went into the tunnel with his accomplice, Mr. Dunn. Before he was associated with the project, Travers had been in the Union Army as an enlisted officer. In a letter that was found mailed to his sister, he wrote that the men always heard groans of dying men inside the tunnel.

No matter how often Travers told his men that the sounds were made by the wind, they wouldn’t listen. However, when Travers entered the tunnel to investigate one evening, he was shocked to discover that the men were indeed telling the truth: there was someone groaning in the depths.

But the worst was yet to strike. On October 17, 1868, a massive explosion occurred inside the tunnel, blowing apart the surface pumping station. Thirteen miners died in the carnage that ensued. The central shaft where the miners worked was filled with debris, making escape impossible.

According to a correspondent from The North Adams Transcript, Mallory, a miner, was lowered into the gaping shaft using a rope. He was to look for any signs of survivors. However, by the time he was bought back to the surface, he was barely conscious due to the fumes. As for the survivors, he gasped. “No hope.”

Without a pumping station, however, the shaft was soon filled with water. As the water rose, did the bodies of some miners. More than a year later, however, it was discovered that not all men had died in the initial explosion. Some had built makeshift rafts and perished as the toxic air overwhelmed.

Read More: The Melon Heads Of The United States: Who Are They?