In May of last year, a remarkable scene unfolded at the 2023 PEN America literary gala as Salman Rushdie, nine months removed from the harrowing knife attack that nearly claimed his life, made an unexpected appearance.

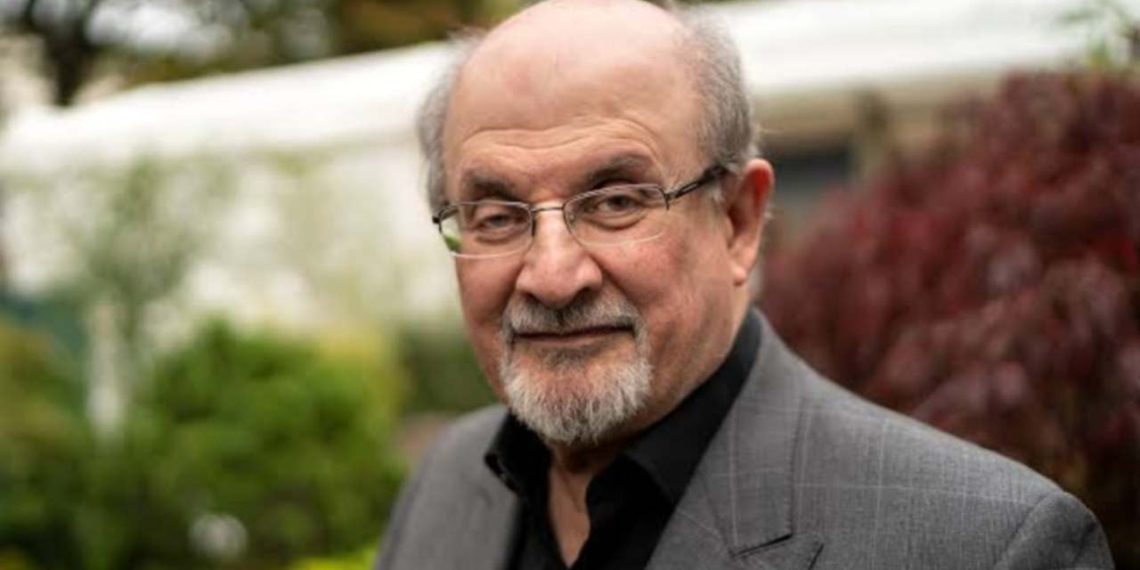

Despite his weakened voice and visibly diminished physique, accentuated by a lens blackening out his right eye – a casualty of the assault – Rushdie’s spirited persona shone through.

His opening remarks, punctuated by a spontaneous and lively joke, dispelled any doubts about his enduring exuberance.

“I want to remind people in the room who might not remember that ‘Valley of the Dolls’ was published in the same publishing season as Philip Roth’s ‘Portnoy’s Complaint,’” he said, riffing on an earlier speaker’s mention of Jacqueline Susann’s potboiler.

“And when Jacqueline Susann was asked what she thought about Philip Roth’s great novel” — with its enthusiastically self-pleasuring main character — “she said, ‘I think he’s very talented but I wouldn’t want to shake his hand.’”

Rushdie’s signature improvisational literary wit was on full display during the solemn occasion of accepting PEN America’s Centenary Courage Award.

His acceptance, amidst the backdrop of his near-fatal attack, served as a triumphant declaration that neither his spirit nor his commitment to living openly had been quenched, even decades after the issuance of the infamous fatwa by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran over his novel “The Satanic Verses.”

Scheduled for release on April 16, Rushdie’s latest book, “Knife,” delves into the chilling narrative of the assault and its aftermath, underscoring the severity of his injuries.

However, it transcends mere recounting, evolving into a poignant love story. The narrative attributes much of Rushdie’s recovery and resilient outlook to the unwavering support and bravery of his wife of three years, the esteemed poet and novelist Rachel Eliza Griffiths.

Their serendipitous encounter at an event in 2017, where flirtation ensued over drinks at an after-party, culminated in a memorable moment when Rushdie walked straight into a glass door while attempting to follow her onto the roof deck – a humorous anecdote now etched into their shared history.

“I wanted to write a book which was about both love and hatred — one overcoming the other,” Rushdie said in a recent interview. “And so it’s a book about both of us.”

Nearly a year had elapsed since his memorable PEN speech. Seated in the Manhattan office of his long-standing agent, Andrew Wylie, Salman Rushdie appeared notably more robust than during his onstage appearance.

Despite ongoing physical challenges stemming from the attack, such as bouts of fatigue and lingering nerve damage affecting his speech and hand, Rushdie exudes resilience.

While his right eye remains permanently unusable, his voice has regained its rich timbre and his characteristic quick wit shines through.

His relaxed demeanor and agile mind, effortlessly weaving in references to literature and popular culture, evoke a sense that his vast repository of knowledge is readily accessible, akin to a personalized Google service.

While initially contemplating the title “A Knife in the Eye,” a nod to the severity of his injuries, Salman Rushdie ultimately opted for a single-word title, as sharp and impactful as the object itself: “Knife.”

Exploring the multifaceted symbolism of the word, Rushdie highlights its dual nature as both a weapon and a recurring motif in various forms of art – from literature to cinema to visual arts.

Within the pages of Rushdie’s book, “Knife” transcends its literal meaning, serving as a potent metaphor for gaining insight and understanding.

“Language can be that kind of knife, the thing that cuts through to the truth,” Rushdie said. “I wanted to use the power of literature — not just in my writing, but in literature in general, to reply to this attack.”

The attack came seemingly out of nowhere, long after the threat to his life appeared to have diminished.

While residing in London at the time of the fatwa, Rushdie was under constant Special Branch protection, a mandate from the British government. However, he opted to forgo this protection when he relocated to New York over two decades ago.

“You know, America’s view of security is, if you think you’re in danger, get a gun,” Rushdie said. “Or at least get somebody with a gun. But for me, it was a kind of freedom.

At least it allowed me to make my own choices.” For all that time, he said, “everything felt pretty normal. I felt like I was living a fairly conventional writer’s life.”

On August 12, 2022, during a speech at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York, Salman Rushdie found himself unexpectedly under attack.

Ironically, the topic of his discussion was the City of Asylum program, aimed at providing refuge to threatened writers.

A black-clad assailant, later identified as Hadi Matar, charged onto the stage wielding a knife. Matar, who has pleaded not guilty to charges of second-degree assault and second-degree attempted murder, awaits trial.

The frenzied attack left Rushdie with profound injuries. The blade struck him a total of 10 times, severing tendons and nerves in his left hand, piercing his right eye, and inflicting wounds across his neck, thigh, hairline, and abdomen.

In the terrifying moment before the assault, Rushdie recalls two distinct thoughts: the acknowledgment of death’s arrival – “So it’s you. Here you are.” – and the incredulity that such an event would unfold after years of relative calm – “Really? Why now, after all these years?”

Amidst the onslaught of blows, bystanders rushed to Salman Rushdie’s aid, led by Henry Reese, 73, co-founder of the City of Asylum program.

Reese, who was conducting an onstage interview with Rushdie at the time, sustained injuries himself – a shallow knife wound and a badly bruised right eye – as he bravely subdued the assailant.

“If it hadn’t been for Henry and the audience, I wouldn’t be sitting here writing these words,” Rushdie says in the book.

“That Chautauqua morning I experienced both the worst and best of human nature, almost simultaneously.”

“The gravity of his wounds was just insane, like something out of a horror film,” said Andrew Wylie, who has represented the author for decades.

Rushdie remained in the hospital for nearly two months. Even after returning home, he had vivid, horrific dreams — about the blinding of the Duke of Gloucester in “King Lear,” about the opening sequence of the Luis Buñuel movie “Un Chien Andalou,” in which a cloud drifting across the moon becomes a razor blade slicing an eye.

He had medical appointments almost every day, different specialists for each affected body part. “Everyone had to sign off on the various repair jobs,” he said.

Rushdie had been nurturing an idea for a novel before the attack. However, upon attempting to revisit the project post-assault, he found himself unable to proceed.

“When, finally, it felt like the juice was beginning to flow again, I went and opened up the file that I’d had, and it just seemed ridiculous,” he shared. “It just became clear to me that until I dealt with this, I wouldn’t be able to write anything else.”

“Knife” emerges as a visceral and deeply personal narrative, a departure from Rushdie’s earlier memoir, “Joseph Anton,” published in 2012.

Unlike “Joseph Anton,” which was written in the third person to create distance between the author and his story, “Knife” offers an intimate portrayal, placing Rushdie front and center amidst the unfolding events.

“I wanted it to read like a novel,” Rushdie explained of the earlier book. But “Knife” is different.

“This is not novelistic. I mean, somebody sticks a knife in you, that’s pretty personal. Pretty first person,” he said.

Within the pages of “Knife,” Rushdie crafts a poignant passage where he envisions interrogating his assailant, purposefully avoiding direct mention of the individual by name. Instead, he refers to him cryptically as “My Assailant,” “my would-be Assassin,” and “the Asinine man who made Assumptions about me, and with whom I had a near-lethal Assignation.”

To maintain a semblance of decorum, Rushdie opts for the more neutral designation of “the A,” yet acknowledges that his private moniker for the assailant remains his personal prerogative.

What emerges from Rushdie’s reflection is not a surge of anger, but rather a complex array of emotions.

“Obviously I’m not particularly pleased about him,” he said. “And if I gave it some attention, I probably am angry. But where does that get you? Nowhere. And it also becomes a way of being captured by the event, you know, to be possessed by a kind of rage about it.”

His therapist has helped, he said, as has a natural steeliness.

“Sometimes you don’t know how resilient you are until the question is asked, until you’re obliged to face very tough things,” he said.

Rushdie shares a close bond with his two sons, Milan and Zafar, while his affectionate regard for Griffiths signifies a newfound contentment in his later years, following a colorful romantic history that includes four previous marriages, notably with novelist Marianne Wiggins and celebrity chef Padma Lakshmi.

Reflecting on his family’s response to Griffiths, Rushdie recalls their collective sentiment of relief, as if to say, “Finally.”

While Rushdie primarily identifies as a novelist, he has long felt compelled to engage with public issues.

Even before the fatwa, he felt a sense of duty to participate in matters of societal importance. Serving as president of PEN America for years, Rushdie stood at the forefront of the organization’s advocacy for free speech.

When presented with an award by PEN America’s then-president, Ayad Akhtar, Rushdie was lauded for his unwavering commitment to freedom and for broadening the world’s imaginative horizons, even at great personal cost.

However, despite being recognized as a symbol of freedom by many, Rushdie himself does not perceive himself as such.

“I’ve never felt symbolic. I felt — you know, I’m just here.” He laughed. “I’m just Ken.” (This was an allusion to Ryan Gosling’s showstopping song at the Oscars, the night before the interview.) “I’m just me. I’m just somebody who’s trying to be a writer, trying to do his best. And that’s all I’ve ever wanted to be.”

In June, Rushdie will reach the age of 77, a milestone that carries particular weight given that it matches the age at which his father passed away—a moment of reflection that holds significance for anyone. However, for Rushdie, this juncture is amplified by the recent trauma he has endured.

“I came very close to dying,” he said. “And when you get that close, when you get a really good look at it, it stays with you. It’s much closer to the front of my head than it used to be.”

Yet he’s not afraid. “Did you ever see the musical ‘Spamalot’?” he continued. “There’s a wheelbarrow of plague victims being wheeled across the stage. And when they get to the middle of the stage they all jump off the wheelbarrow and sing this song, ‘He Is Not Dead Yet.’

“Either you succumb to the fear of death, or you don’t,” he said.