Northern Ireland legislators were set to appoint an Irish nationalist as First Minister on Saturday, marking a historic shift in a province created a century ago to uphold the supremacy of pro-British unionists.

Michelle O’Neill’s rise to the position is the most recent indication of her Sinn Fein party’s growing influence across the island. The party now envisions a united Ireland as a tangible possibility.

Michelle O’Neill’s promotion became feasible this week as the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) concluded a two-year boycott of the power-sharing government. The boycott had posed a threat to the political settlement crucial to the 1998 peace deal.

“Good Morning World,” shared Sinn Fein President Mary Lou McDonald on social media platform X, directing attention to an RTE article stating that Northern Ireland was poised to become the epicenter of a political earthquake.

O’Neill and McDonald symbolize a shift to a new generation of Sinn Fein politicians not directly implicated in the region’s decades-long conflict between Irish nationalists and pro-British unionists. Formerly linked to the Irish Republican Army (IRA), Sinn Fein was once ostracized but has become the most favored party in the Irish republic ahead of next year’s elections.

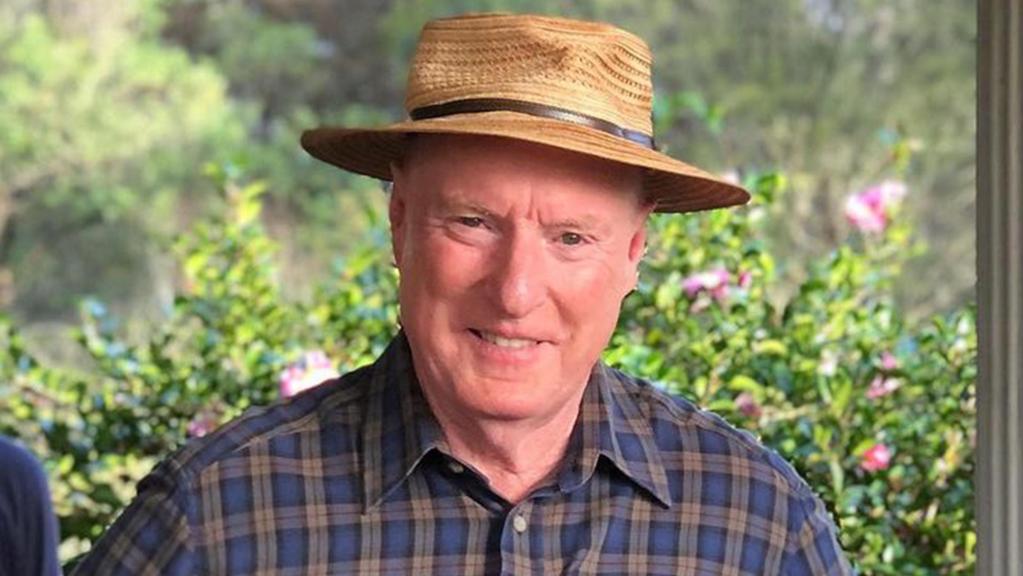

The regional assembly is set to confirm O’Neill, 47, as First Minister after 1300 GMT. Although the compulsory coalition grants equal power to the DUP’s deputy First Minister, the symbolic weight has always rested with the title of First Minister. While Sinn Fein emphasizes unity, all Northern Ireland politicians face intense pressure to address everyday concerns amid the two-year hiatus, straining public services.

A unity referendum lies within the British government’s discretion, with opinion polls consistently indicating a majority favoring the United Kingdom. The assembly will also address calls for reform to prevent prolonged power-sharing disruptions, as the largest party on either side has frequently suspended it since the establishment under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

Both the Irish and British prime ministers have expressed openness to considering reforms in the political architecture once the devolved government is operational.

“They’re fed up,” 40-year-old lawyer Tara Walsh said of the general mood on the streets of Belfast. “People want change.”