The relationship between Hayao Miyazaki and Yoshiyuki Tomino is a tale of fascinating contrasts, professional rivalry, and mutual respect. Both of these legendary filmmakers hail from the same era, yet their creative philosophies and careers diverged significantly.

Miyazaki is known for his universally beloved films, including My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away, while Tomino’s Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam goes into the darker, grittier aspects of human nature and the trauma of war. This fundamental difference in tone and subject matter has led to a relationship defined by both admiration and professional envy, with the two men creating iconic works in their respective fields.

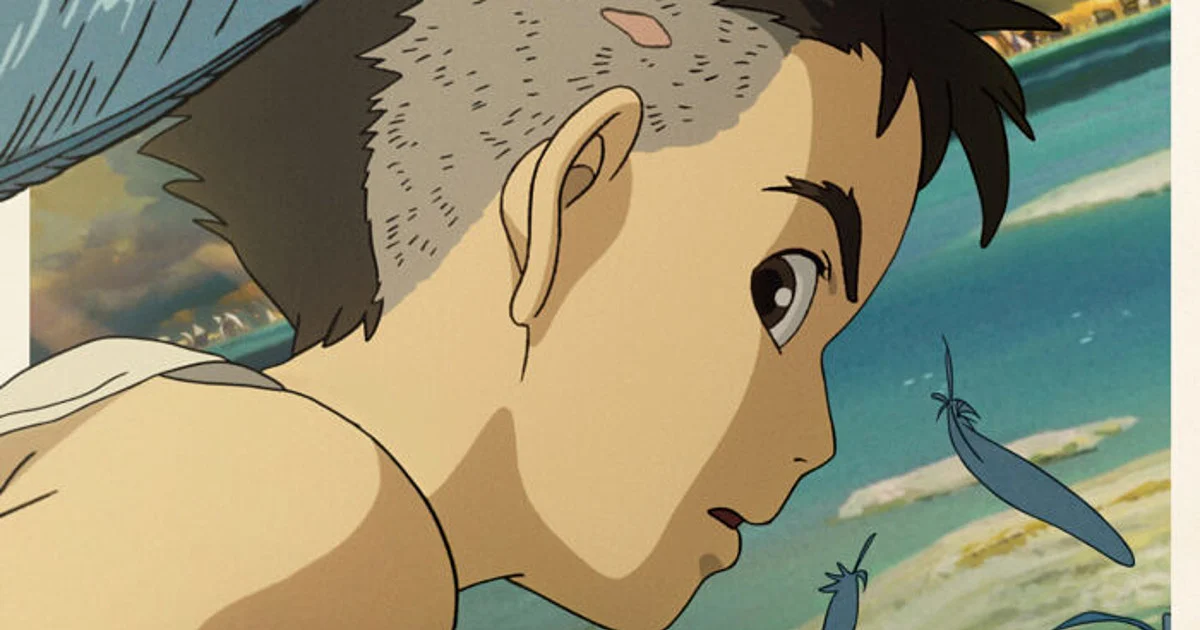

Despite their differences, Tomino has spoken candidly about his feelings towards Miyazaki’s work. In an interview at the Niigata International Animation Film Festival in August, Tomino was asked to share his thoughts on Miyazaki’s films. He admitted that while he didn’t resonate with most of Miyazaki’s work, he had a deep appreciation for The Boy and the Heron. Tomino admired the film’s boldness, noting that the lack of a happy ending was a rare and courageous choice in animation.

A Professional Rivalry Driven by Respect

He stated that such a decision couldn’t be made by someone who was merely a craftsman but by a true auteur. For Tomino, Miyazaki’s approach to storytelling, especially in The Boy and the Heron, showed a level of creative control and vision that elevated him beyond the typical filmmaker. Tomino even compared him to literary greats like Victor Hugo, signaling his respect for Miyazaki’s ability to break conventions and challenge expectations.

Tomino’s respect for Miyazaki, however, is not without complexity. While he acknowledged Miyazaki’s artistic skills, he referred to him as an “enemy” in a professional sense. Tomino explained that the presence of Miyazaki, a filmmaker whose talents he could never surpass, served as a constant source of motivation throughout his career. Instead of bitterness, this rivalry appeared to drive Tomino to continually strive for excellence in his own work.

Tomino has even mentioned in previous interviews that his ambition to compete with Miyazaki pushed him to constantly improve. In 2001, Tomino famously encouraged the younger generation of animators to “crush Miyazaki,” reflecting how this professional competition spurred him on to work harder and achieve greater creative heights.

Despite Tomino’s acknowledgment of Miyazaki’s superior status as an auteur, his comments reflect the deeply personal nature of artistic rivalry. Tomino’s critique of Miyazaki’s broader body of work speaks to the differing philosophies that define their careers. Miyazaki’s films tend to lean on hope, innocence, and positive resolutions, whereas Tomino’s Gundam series is famous for its exploration of darker themes, including the horrors of war and human suffering. While Tomino may not always enjoy Miyazaki’s storytelling, he understands that it is this very approach that has earned Miyazaki his place as a groundbreaking filmmaker.

Tomino’s admiration for The Boy and the Heron and his acknowledgment of Miyazaki’s influence show that despite their artistic differences, the two directors share a mutual respect for each other’s work. Their rivalry, fueled by Tomino’s desire to exceed Miyazaki, has shaped both of their creative trajectories, with each director pushing the other to greater heights.