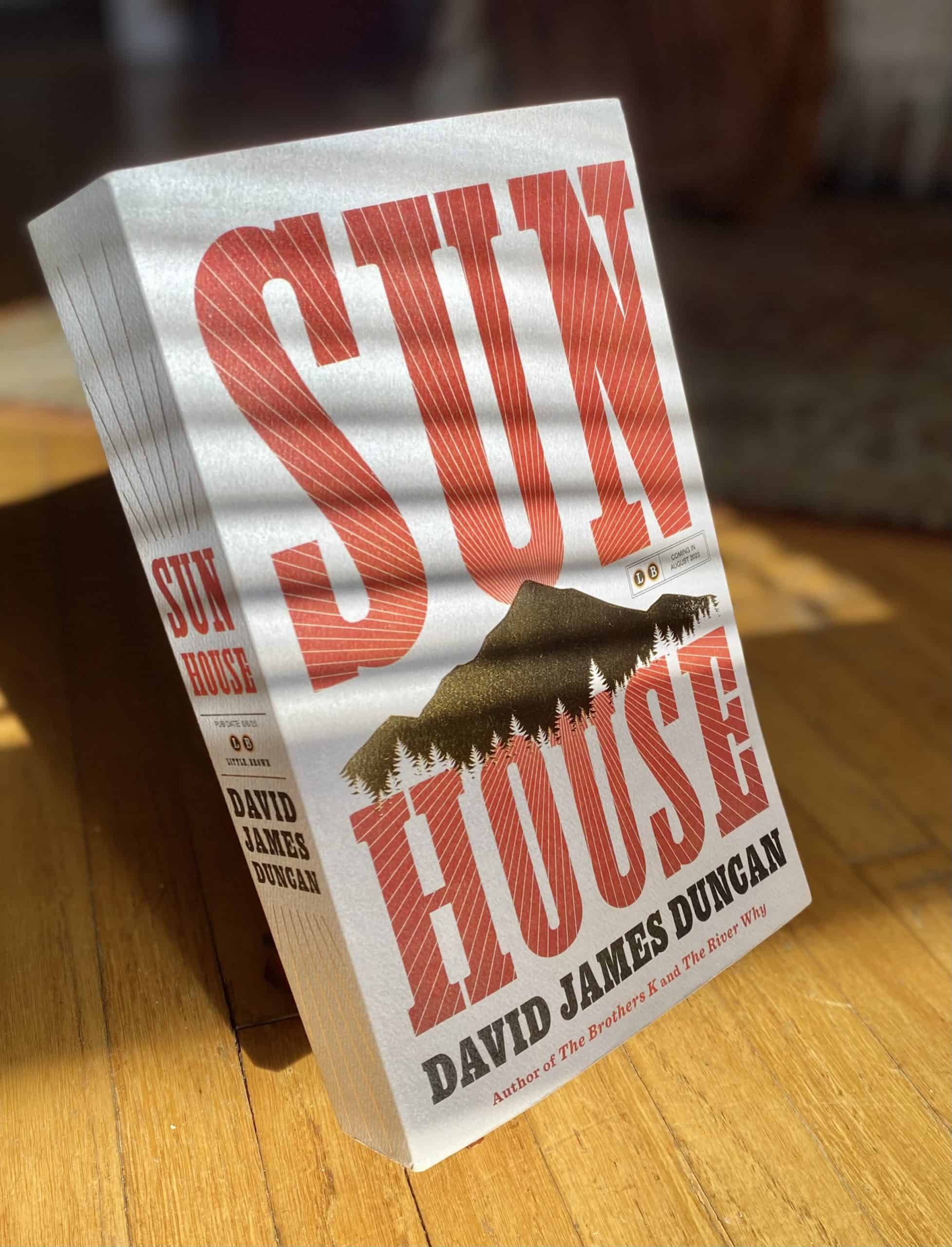

David James Duncan is an American novelist and essayist born in 1952 in Portland, Oregon. His two bestselling novels, The River Why released in 1983, and The Brothers K, released in 1992, received the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Award. Sun House, the third novel of Duncan’s, was released on August 8, 2023by Little, Brown, and Company.

The novel “The River Why “was adapted into a “low-budget film” in 2008, starring William Hurt and Amber Heard. The film rights became the subject of a lawsuit with Duncan alleging copyright infringement on April 30, 2008. The lawsuit was settled later, with the rights returned to him.

Duncan’s short story collection was River Teeth in 1996, and a memoir, My Story As Told By Water, in 2001. In the realm of literature, certain moments transcend mere words on a page, revealing profound dedication, camaraderie, and an unwavering energy that breathes life into a masterpiece.

This narrative unfolds in the world of the highly anticipated book “Sun House,” crafted by the esteemed Montana author David James Duncan. The story behind this opus is one of resilience and redemption, a journey that nearly shattered the author before ultimately saving his soul.

“Sun House”: A Magnum Opus Forged Through Struggle and Redemption

Rewind to New Year’s Eve in 2007. At age twenty-five and unattached, I found myself holed up in a former Forest Service cabin nestled along Montana’s Flathead River, opposite Glacier National Park. Instead of partaking in festivities in the nearby town of Whitefish, I remained ensconced in the cabin’s solitude.

The reason? I was deeply engrossed in Duncan’s acclaimed 1992 novel “The Brothers K.” Isolated from the world for at least a week, I found companionship in the Chance brothers’ journey, as intricately woven by Duncan.

Though my current abode is far from rustic seclusion, my allegiance to the burgeoning following of Duncan remains unwavering. His early works, like the 1983 novel “The River Why,” shed light on the profound bond between the natural world and the human spirit’s longing.

Over the past four decades, Duncan’s literary pursuits have extended to distinguished nonfiction, encompassing essays such as “Bird-Watching as a Blood Sport” and “When Compassion Becomes Dissent.” His literary achievements also include books like “River Teeth” and the National Book Award-nominated “My Story as Told by Water.”

Today, Duncan unveils his magnum opus, “Sun House,” a labor of love that shows sixteen years of dedication. Having nearly 800 pages, the book exudes both expansiveness and compactness, mirroring its title’s musical resonance.

It is the result of tireless days, personal and global upheavals, and an unparalleled depth of compassion and spirituality. Much like “The Brothers K,” once you delve in, it becomes a challenge to put down.

The Cult of Duncan: Navigating Nature and Spirituality Through Literature

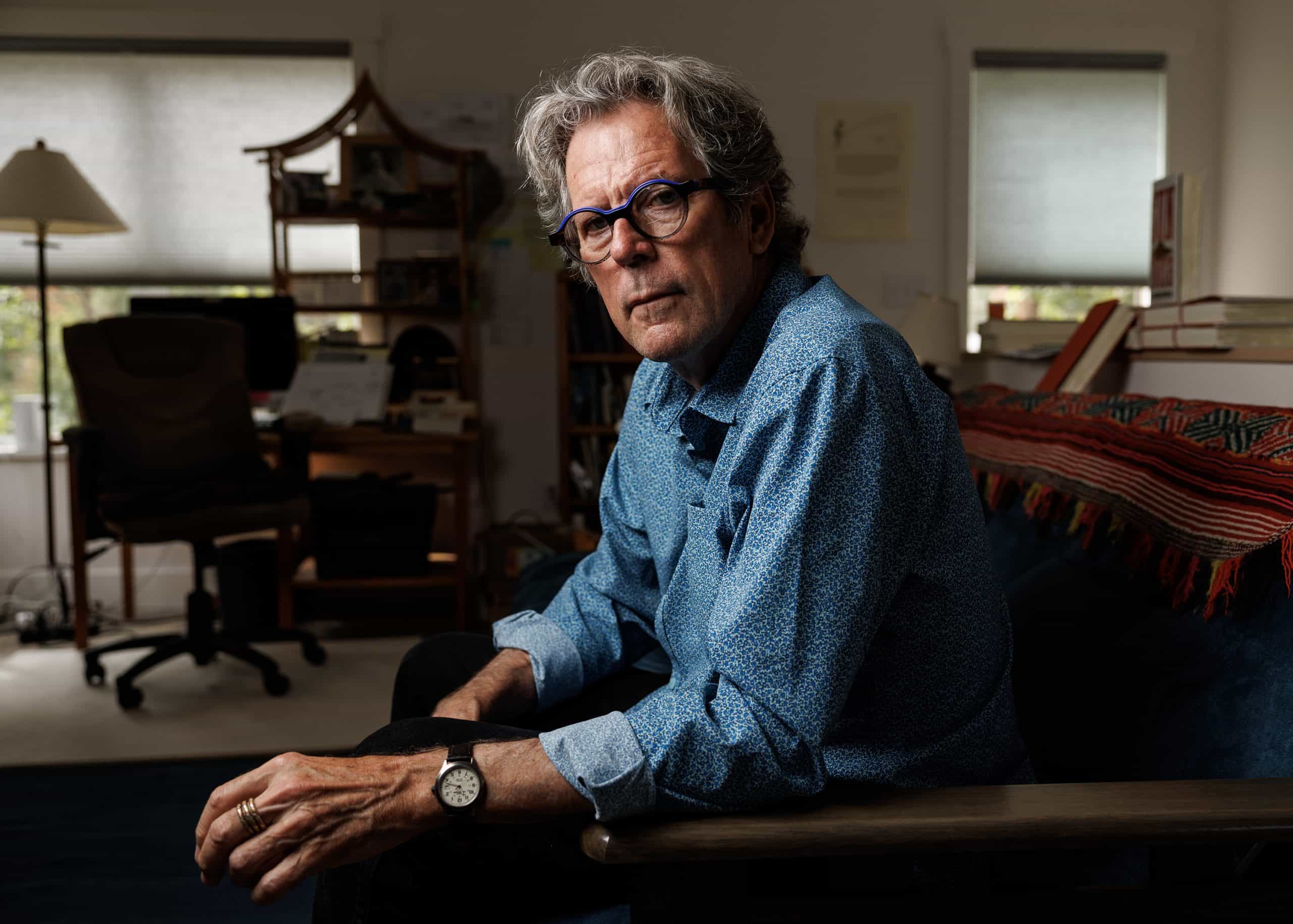

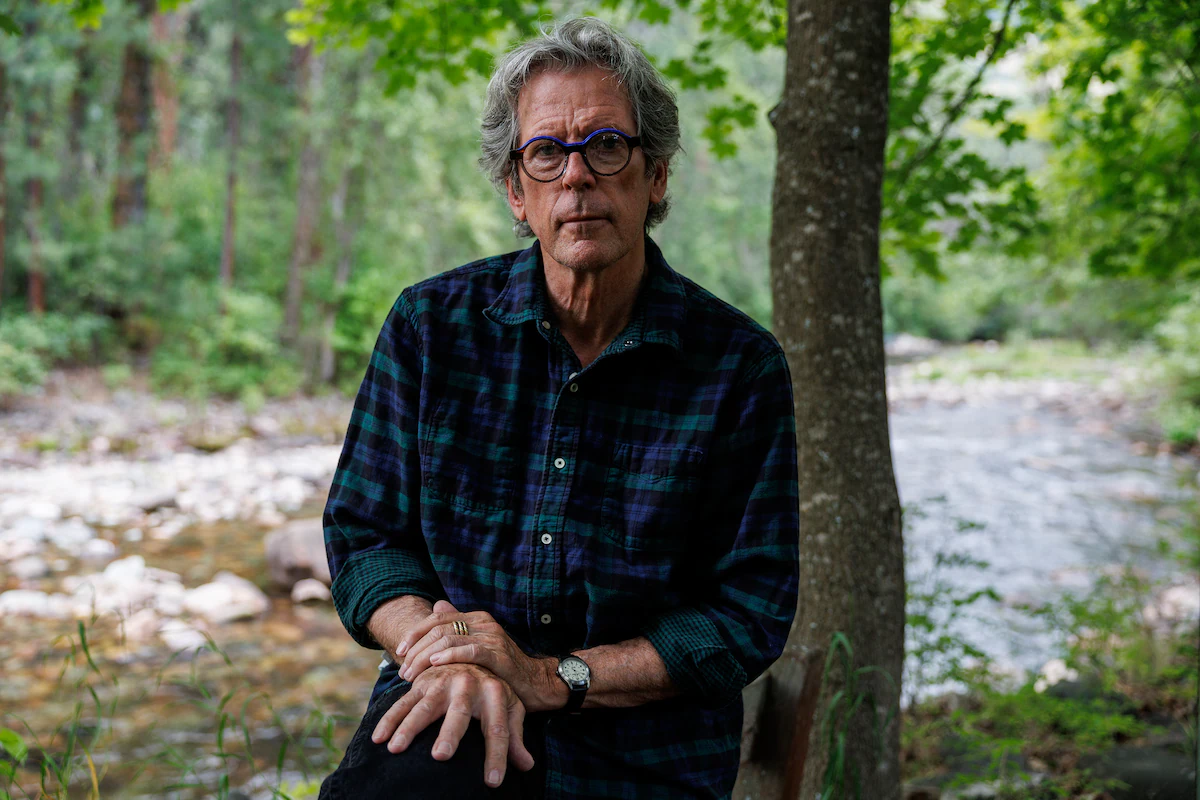

Amid a sweltering July morning in Missoula, I paid a visit to Duncan. The 71-year-old writer, activist, accomplished fly-fisher, and new grandfather set the stage for our conversation about his latest literary opus by welcoming me into his townhome, mere steps away from Rattlesnake Creek. Michael Pietsch, his editor at Little, Brown, aptly refers to “Sun House” as Duncan’s “magnum opus.”

The novel spans the lives, trials, and triumphs of an eclectic ensemble of characters determined to foster a compassionate community in modern-day America. Narrated by the enigmatic Holy Goat, the tale is skillfully interwoven with journal entries, letters, and song lyrics, unraveling the tapestry of disparate lives converging at Elkmoon Beguine & Cattle Company. At this Montana ranch, a new way of life takes root.

As we settled into conversation, Duncan, sporting a button-down shirt, well-worn Levi’s, and blue-rimmed round glasses, demonstrated a commitment to focus by silencing his ringing phone with a pillow toss.

Despite his three-decade-long residence in Missoula, he recently sought solace in this creekside dwelling, emerging from a divorce and a period of personal struggle. The motive behind “Sun House” was a tribute to his daughters, Celia and Ellie, and a broader ode to the upcoming generation.

He shares, “I wrote it for the young, who so many in our anti-culture have betrayed and abandoned, apparently preferring guns, belligerence, destructive work, and an unimaginable future.”

A Literary Sanctuary: How “Sun House” Became Duncan’s Refuge for Recovery

The narrative is guided by eight central characters, including Risa McKeig, a Sanskrit scholar, and Lorilee Shay, a mountain dulcimer player. These characters, particularly Risa and Lorilee, serve as conduits for the story’s electric connectivity. These personalities were drawn from Duncan’s life experiences, a conscious effort to accurately depict the strong women he’s encountered, including his daughters.

However, “Sun House” is not just confined to individual portrayals; it’s a vessel for the myriad subjects Duncan has explored over the years. Beyond that, it’s a potent response to his homeland’s despondency, division, and distractions. At its core lies compassion, the essential element on which the narrative stands.

In a personal encounter with Duncan, one is struck by his profound investment in his work. His words are measured, punctuated by thoughtful pauses. As he reads select passages aloud, his eyes well with tears.

The characters he has brought to life resonate as strongly as the nearby Rattlesnake’s babbling waters. These characters manifest his decades spent writing, teaching, and advocating for the environment.

Duncan’s 2012 collaboration with fellow Montana author Rick Bass in “The Heart of a Monster” exemplified this commitment. A form of storytelling activism, the work protested the creation of an industrial corridor linking the Alberta Tar Sands to Asia through Montana’s vital rivers.

Duncan’s pride in the project’s impact shines through, a testament to the power of civil resistance. This sentiment finds its echo in “Sun House” as Kale, a Montana ranch foreman, wages a battle against land exploitation, aiming to protect the unspoiled wilderness from becoming a playground for the wealthy elite.

Spirituality forms a steady undercurrent throughout the narrative, interwoven through mysticism, poetry, and music, including blues and folk tunes. A notable presence is the verses of Zen poet Gary Snyder.

An entire chapter titled “Second Telling: The One-Book-of-Poems-Long Marriage” pays homage to Snyder’s profound influence. Snyder’s approval and permission to quote from “Axe Handles” resonated deeply with Duncan, a connection that underscores the narrative’s spiritual dimension.

The characters in “Sun House” bear their own burdens of suffering as they embark on new chapters of their lives. Jamey Van Zandt’s life was forever scarred by the loss of his mother on his fifth birthday. Risa’s parents’ divorce left a permanent imprint on her soul. Grady Haynes, a former software executive, achieved heights of success only to lose his sense of purpose.

Some of these struggles mirror Duncan’s own life experiences. He reveals, “I faced one of the most severe heartbreaks as I concluded the first draft about four years ago. I lost my home and my marriage.”

This personal upheaval led to a revelation — an epiphany that brought a change in his life. After years of struggling with health issues, including asthma, Duncan realized his allergic reaction to the horses on his property.

Relocating to his current abode in a serene neighborhood revitalized his health, granting him renewed energy and objectivity to revisit “Sun House.” He meticulously reexamined the manuscript, revisiting every page over two and a half years, pouring his dedication into countless revisions and improvements.

In a serendipitous turn, “Sun House” became more than a literary venture; it became Duncan’s sanctuary for healing. A refuge reminiscent of the Elkmoon Beguine & Cattle Company, where his characters seek solace, the novel served as a healing balm for his personal wounds.

The characters’ journeys of healing through sacrifice — whether trekking to a sacred lake or advocating for the marginalized — resonated deeply with Duncan’s experience.

Their collective odyssey culminates in Elkmoon Beguine, an intentional community of different individuals. This conception draws inspiration from medieval European lay religious communities known as Beguines.

Duncan’s take is an amalgamation of ideas he had in his life, drawing from the works of mystics, poets, and philosophers. “Sun House” encapsulates this eclectic fusion of thought and wisdom, offering readers a glimpse into Duncan’s own transformative journey.

The spiritual essence of “Sun House” extends beyond its pages, providing Duncan with a personal sanctuary akin to Elkmoon Beguine. He reflects, “For me, working on ‘Sun House’ became as literal a refuge as the fictional Elkmoon Beguine & Cattle Company. In a sense, I became the first recipient of their community’s protection.”

As I left Duncan’s presence, the realization dawned that “Sun House” is more than a novel. It’s an invitation into the heart and soul of a dedicated writer, a testament to his commitment to the craft and his indomitable spirit.

Similar to characters who find solace in their sanctuary, Duncan finds respite in creating this sprawling narrative, a journey that nearly broke him but ultimately saved his soul.

Also Read: Oppenheimer Viewer’s Discovery Challenges Christopher Nolan’s Accuracy: A Flaw in Time

The rights to The River Why were not returned to Duncan. Instead, he retained the right to make his own film version of the book, while the filmmakers retained their right to complete their film. I have not finished Sun House, but what I’ve read so far is very compelling.