Most murders can be solved very easily. The crimes follow a pattern, and the motivations are typically obvious. Of course, there are rare incidents that defy the norm, where the murderer is an unknown person or the motive for the crime is peculiar. There have been many murders and crimes that have gone unsolved in recent history. Some of them are more well-known due to the extensive media attention they receive, while others have gained popularity among fans of crime and mysteries because of their notoriety and oddness. The Somerton Man, often referred to as the Tamam Shud Case, is one such unsolved mystery.

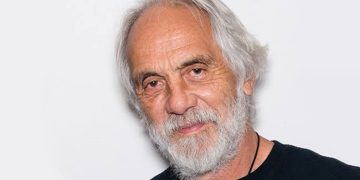

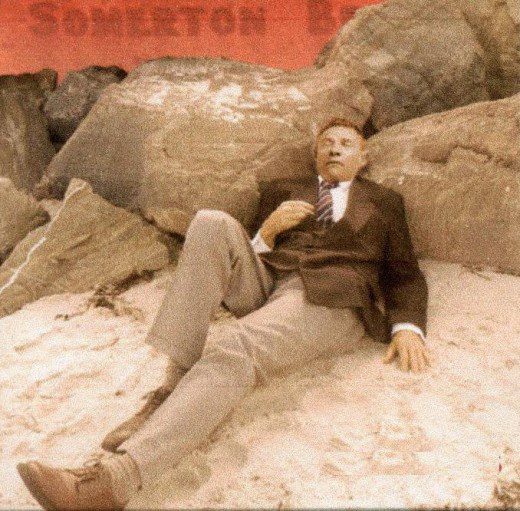

The corpse of a man in his 40s or 45s was found on Somerton Beach, near Glenelg, South Australia, on December 1, 1948. The man was lying on his back, appearing to be asleep. All of the clothing’s labels had been taken off when the body was brought to the coroner’s office, and no papers or other identifying information could be found. This case is so mysterious that we still have no idea what killed him and are even unsure of whether it was a suicide or murder.

Who All Witness The “Unknown Man” Lying On The Beach?

Several witnesses reported to the police that they had seen the man strolling the beach the previous evening, and further witnesses concurred that they had seen him lie down, possibly taking a sleep. The man’s shoes were spotless as if he had never stepped on the sandy beach and had somehow been transferred just there.

Jewelry designer John Bain Lyons and his wife took a walk on Somerton Beach on a pleasant November evening in 1948. A few minutes south of Adelaide is the seaside resort of Somerton Beach. They observed a well-dressed man sitting on the sand with his head resting on a sea wall as they made their way toward Glenelg. He was lying down approximately 20 yards away from them, his feet crossed and his legs extended. The man raised his right arm and let it fall back onto the ground as the couple watched. Lyons speculated that the man might be attempting to light a cigarette while drunk.

Another pair saw the same man still lying in the same posture thirty minutes later. The woman was able to see above that he was neatly attired in a suit, with neat new shoes shined to a mirror gloss attire for the beach. He was still, and his left arm was outstretched on the sand. The pair concluded that he was merely dozing off while being swarmed by insects.

The coroner was unable to determine the man’s identity, cause of death, or whether he was the same man because no one had seen his face when he was last seen alive at Somerton Beach on the evening of November 30.

What Did The Autopsy Of The Body Say?

The body arrived at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. There, Dr. John Barkley Bennett estimated the death to have occurred no before than 2 a.m., recognized heart failure as the most likely cause of death, and indicated that he believed poisoning. Tickets from Adelaide to the beach, two combs, some matches, a package of gum, and a pack of Army Club cigarettes that contained seven cigarettes of a more costly brand called Kensitas.

There was no ID, no wallet, and no cash. None of the man’s clothing had name tags; in fact, all but one of them had the maker’s label skillfully removed. A nice repair had been made to one of the pant pockets using an unusual orange thread. Police said at the inquest that a tailor believed his coat originated in the US and that the bag contained clothing with torn-off labels.

The authorities had followed up on all of their best leads regarding the identity of the deceased when a complete autopsy was performed a day later, and the postmortem findings were not very illuminating. It showed that the body’s pupils were “smaller” and “strange” compared to what they should have been.

The man died roughly three to four hours after eating a pasty, according to the autopsy, although testing did not turn up any evidence of a foreign substance in the body. The pasty was not thought to be the culprit, even though poisoning remained the leading theory. It also showed that the man had spittle on the side of his mouth as he lay there and that “he was certainly unable to swallow it.” His liver was swollen by blood clots, and his spleen “was shockingly huge and hard approximately three times normal size.”

To reexamine the body and the deceased man’s belongings, the police had hired John Cleland, an emeritus professor of pathology at the University of Adelaide. Four months after the body was discovered, in April, Cleland’s investigation turned up one more piece of evidence, which turned into the most puzzling of all. The dead man’s pants had a little pocket sewed into the waistband, which Cleland found.

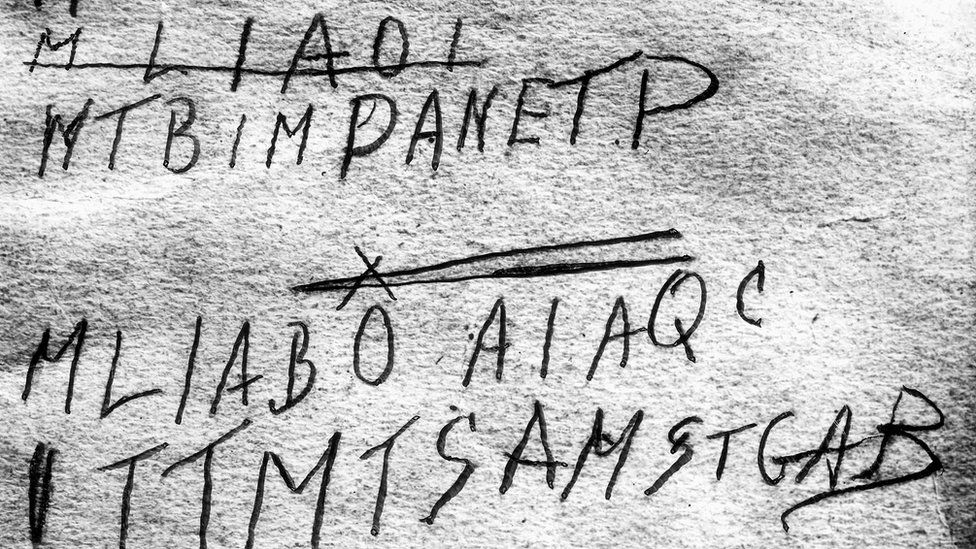

Although it had gone unnoticed by earlier examiners and has been referred to in various versions of the case as a “hidden pocket,” it appears to have been designed to contain a fob watch. A tiny piece of paper was securely curled inside, and when it was unfolded, it revealed two words typeset in a complex printed script. “Tamám Shud” was written in the paper, which means “It is ended” or “Finished” in Persian, which was later discovered to be from a rare New Zealand edition of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.

Personal Belongings of The Dead Unidentified Man

The copy of Rubaiyat from which the page was torn was found after police made a public appeal. On the 23rd, a Glenelg man met police with a 1941 edition of Edward FitzGerald’s (1859) translation of Rubaiyat, which Whitcombe and Tombs in Christchurch, New Zealand, had published. The Glenelg man had not thought the book might be related to the case until he came across an article in the newspaper the day before.

Lionel Leane, a detective sergeant, carefully examined the book. He almost immediately discovered a phone number written in pencil on the back cover. Despite being unlisted, the phone number turned out to belong to a young nurse who resided close to Somerton Beach.

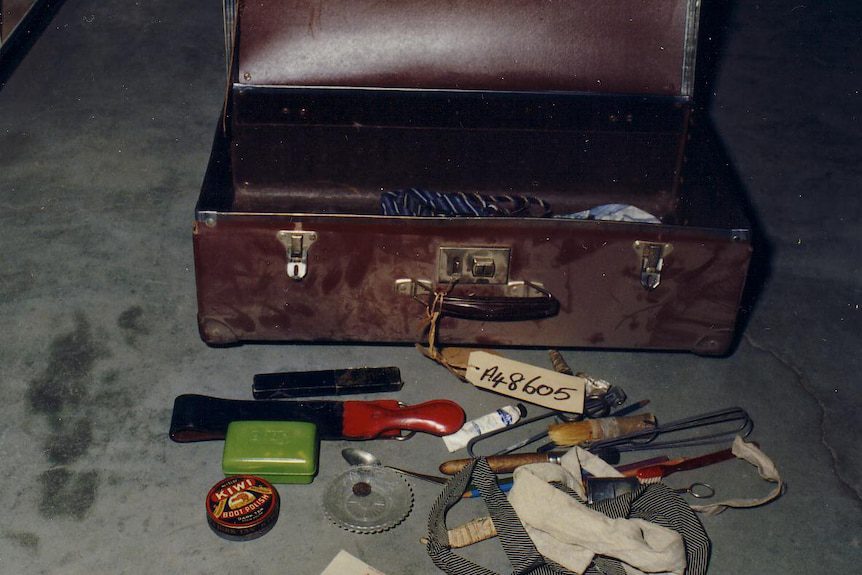

The South Australia police examined and essentially ruled out every lead they had by January 11. The scope of the investigation was now expanded to find any unclaimed personal items, possibly even luggage, that might indicate that the deceased had traveled from another state. This required searching kilometers of hotels, dry cleaners, lost property offices, and train stations. However, it did have an impact. Brown luggage that had been left in the cloakroom of Adelaide’s main train station on November 30 was displayed to detectives on December 12.

There was a reel of orange thread in the case that had been used to mend the deceased’s pants, but it had been meticulously removed from the case. There was an identical reel of orange thread in the case that had been used to mend the deceased’s pants, but the owner’s identity had been meticulously scrubbed from the reel. The case has no labels or markings, and one side’s label was torn off.

The Discovery of An Unknown Man In 2022!

Professor Derek Abbott of the University of Adelaide and retired Australian policeman Gerry Feltus, who wrote the only book on the subject that has been released so far, have made particularly helpful headway in solving the case.

Using hairs saved when authorities created a plaster cast of the Somerton Man’s face, Derek Abbott was able to analyze the DNA of the subject. He used the DNA to create an expanded family tree in collaboration with famous US forensic analyst Colleen Fitzpatrick, who specializes in cold cases. And the two reduced the list of 4000 names to just one: Carl Webb. The man’s living relatives were then located, and their DNA was used to authenticate his identification.

Webb’s last known papers, which date to April 1947, show that he left his wife Dorothy “Doff,” who then filed for divorce. There is no recorded record of Webb’s death. Dorothy supposedly resided at Bute, South Australia, 144 kilometers away from Adelaide, in 1951. Abbott claimed that Webb may have attempted to find her.

Though The Somerton man is now identified, the cause of his death remains unknown.