On February 22, 1936, a multitude assembled at George Washington’s childhood residence near Fredericksburg, Virginia, commemorating the 204th anniversary of his birth.

The highlight of the event at Ferry Farm, amidst ceremonies like dedicating 200 cherry trees along the path to Fredericksburg, occurred at 2:30 PM.

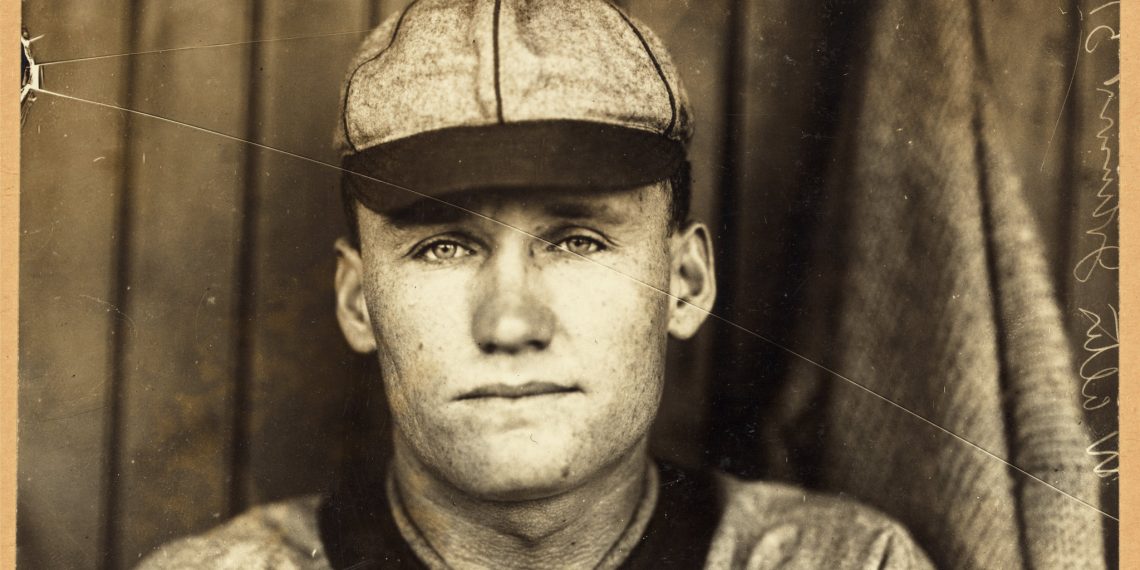

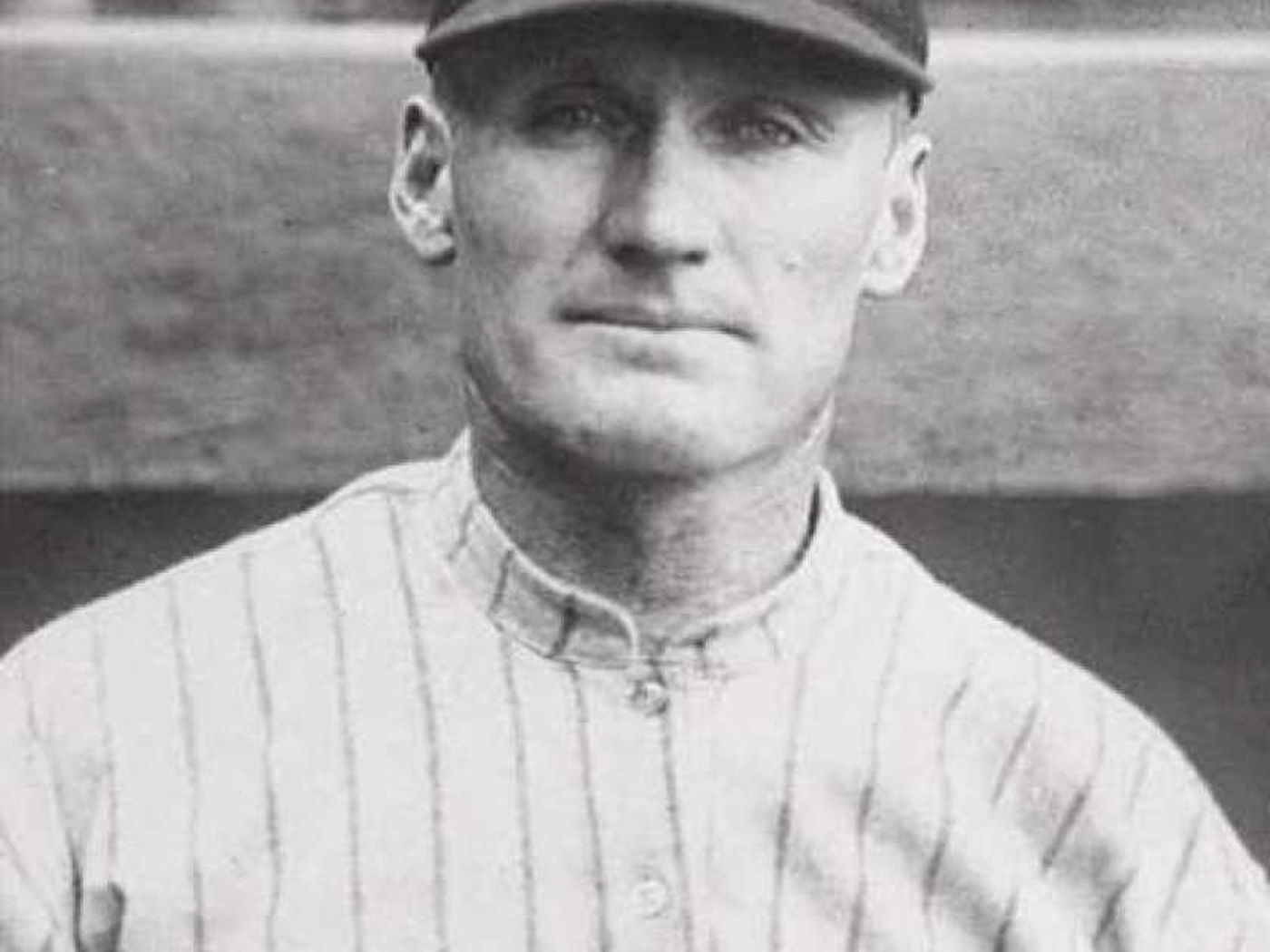

Former Washington Senators’ pitching legend, Walter Johnson, endeavored to replicate Washington’s fabled childhood feat of hurling a silver dollar across the Rappahannock River. Legend has it that Washington achieved this remarkable toss in his youth.

Johnson, aged 48 at the time, had recently been elected as part of the inaugural five-man class of the Baseball Hall of Fame earlier that month.

This honor came after his resignation as manager of the Cleveland Indians the preceding year. Remarkably, during the festivities, Johnson successfully cleared the river twice with his throws.

“He threw it over with the same easy grace he once used in fanning Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and “Ping” Bodie, and so doing he brought to Fredericksburg something of that joy that was denied to Mudville when the mighty Casey struck out,” Edward T. Folliard, staff correspondent for The Washington Post, reported from the scene.

Thanks to a politician’s bold wager and Johnson’s participation, the stunt — while doing little to clear up the veracity of the legend — sparked controversy and attracted national interest.

The apocryphal tale of Washington throwing a silver dollar across the Rappahannock can indeed be traced back to Parson Weems, Washington’s original biographer.

However, in an 1826 essay by George Washington Parke Custis, Washington’s step-grandson, the story was recounted with Washington throwing a piece of slate, not a silver dollar, across the Rappahannock. Over time, the river in the legend’s retellings was often changed to the Potomac.

Walter Johnson, who retired as a player in 1927 and later managed the Senators and Indians until 1935, was indeed familiar with the tales of George Washington’s physical prowess. These stories were likely part of the cultural lore of the time, showcasing Washington’s legendary strength and abilities.

In a 1932 interview with The Post, Walter Johnson mentioned the famous story of George Washington throwing a silver dollar across the Potomac, noting that whether true or fiction, it indicated Washington’s reputation as an athlete, even as a boy.

Johnson also stated that he would encourage his five children to enter the newspaper’s George Washington Bicentennial essay contest.

Four years later, Walter Johnson accepted an invitation from Fredericksburg officials to attempt to reenact George Washington’s feat on the latter’s birthday.

He agreed to participate in the celebration organized by the Fredericksburg Chamber of Commerce, with the condition that someone else provided the dollar and he wouldn’t be asked to wear a colonial costume.

The celebration in Fredericksburg gained national attention when New York Rep. Sol Bloom offered 20-1 odds that Walter Johnson would not succeed in his attempt to reenact George Washington’s feat.

Bloom, who was also the director of the George Washington Bicentennial Commission, believed that the myths surrounding Washington, such as the cherry tree story and the tale of him throwing an object across the Potomac or the Rappahannock, actually detracted from his true legacy.

In 1934, Bloom wrote a book of questions and answers concerning Washington, in which he asserted that Washington did not perform such feats.

Sol Bloom expressed his disbelief in the feat, calling it preposterous and ridiculous. He pointed out that not only was it physically impossible, but also that if you examine the story closely, Washington would have been about 10 years old when the supposed miracle was said to have occurred.

In Fredericksburg, officials initially estimated the width of the Rappahannock at the point near Ferry Farm where Johnson would attempt his throw to be between 350 and 375 feet.

For context, the longest baseball throw on record was 426 feet, achieved by former major league outfielder Larry LeJeune at a contest in Cincinnati in 1910.

Walter Johnson expressed his confidence, stating, “Maybe I can’t throw that far, but there’s one thing certain, if George Washington did it, I can.” This highlights his determination to attempt the feat in honor of Washington’s legacy.

Sol Bloom found himself inundated with phone calls and telegrams from people interested in taking him up on his wager, including Fredericksburg Chamber of Commerce President Ben Pitts, who deposited a certified check for $5,000 in a local bank.

Bloom sought to clarify the terms of the bet, arguing that the Rappahannock was much wider in Washington’s time, estimating it to be closer to 1,500 feet across then, and had gradually become narrower over the years.

He even produced a London cable stating that measurements on Virginia maps in the British public record office listed the river as more than 1,300 feet wide in Washington’s era.

“Maybe Johnson or someone else can throw a dollar over the river today, but they couldn’t do it over the river that ran by the farm in Washington’s day,” Bloom said. “And that’s my bet. Washington didn’t do it and no one else can. The bet still is open for anyone who can throw 1,300 feet.”

“If Bloom wants Walter Johnson to throw a silver dollar 1,500 feet and the natives of Fredericksburg expect him to throw it 375 feet or less, it would appear that all bets are off.”

Walter Johnson humorously wrote to Fredericksburg officials, stating,

“I am still practicing with a dollar against my barn door. Arm getting stronger, barn door getting weaker.”

This demonstrates his dedication to preparing for the reenactment of George Washington’s legendary feat.

Two days before the celebration, Fredericksburg residents made failed attempts to reach the other side of the Rappahannock by showering bushels of iron washers into the river.

Surveyors had calculated the span of the river where Johnson would attempt his throw to be 272 feet. The anticipation was palpable in town ahead of the Hall of Famer’s arrival.

“Tense excitement pervaded this gayly bedecked little city tonight, on the eve of what promises to be a momentous test of an American legend,” the New York Times reported.

“Some visitors arrived today, but the influx was nowhere near the proportions expected tomorrow forenoon. Local merchants are looking forward to a flourishing business when the visitors swell the town to twice or three times its normal population.”

On the day before the celebration, Johnson spent his time practicing on the Potomac River in D.C., where he reportedly tossed a silver dollar a distance of 300 feet.

Although Sol Bloom did not make the trip to Fredericksburg for Washington’s birthday celebration, he sent Johnson a silver dollar coined in 1796 to use for the occasion.

“Walter, there is no one in the world who wishes you more success tomorrow than I do at Fredericksburg when you will try to throw a silver dollar across the Rappahannock,” Bloom wrote.

“After you have warmed up and have two strikes and three balls on the other fellow, use this dollar, because I believe that as the eagle on this dollar is in flight it might bring to you the good luck that millions of people throughout the country are wishing you, and the eagle in its flight might assist in carrying this across the Rappahannock.”

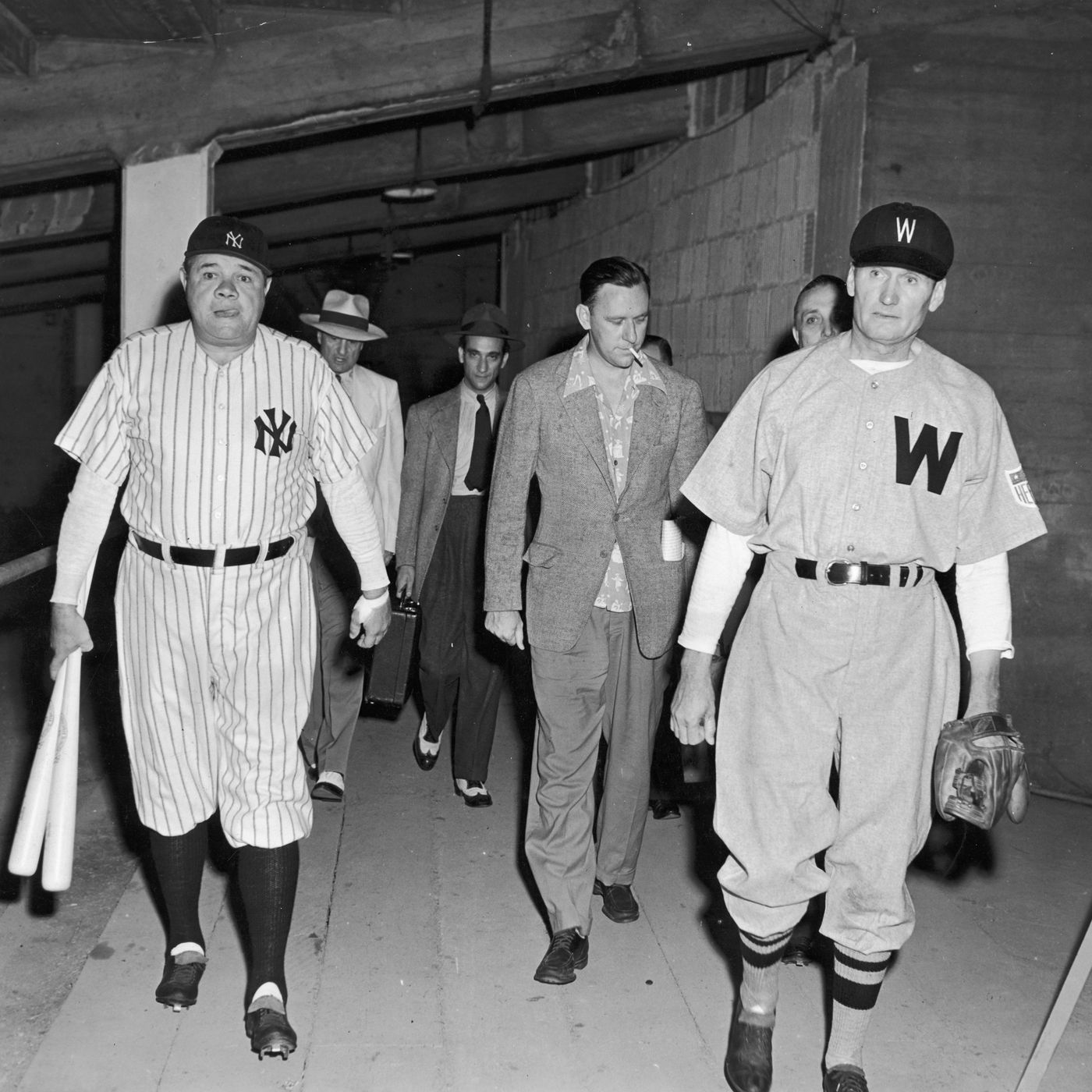

On the big day, with Senators broadcaster Arch McDonald providing play-by-play from the muddy banks of the Rappahannock for a national audience on CBS Radio, Walter Johnson made two practice throws.

His first attempt fell about 10 feet shy of clearing the river. However, his second attempt was greeted with a cheer from the thousands of onlookers on the other side, and it sent a group of people scrambling after the souvenir.

Pitts then handed Walter Johnson a silver dollar for the official toss, marking the culmination of the event.

“Johnson dug his toe in the mud, leaped forward a couple of times, whip-lashed his arm as he used to do in the old days, and the silver dollar sped across the Rappahannock,” The Post reported.

“It glinted in the sun as it traveled. It landed against a gasoline tank and was picked up by Peter Yon, a stonemason.”

A local said,

“Well, that makes a bum out of Sol Bloom.”

H.J. Eckenrode, a Virginia historian and the chief judge of the event estimated that the dollar traveled 317 feet, adding to the excitement of the moment. Despite the outcome, Sol Bloom, who didn’t pay out any bets, sent Walter Johnson another telegram, perhaps to acknowledge his effort or to comment on the result.

“Congratulations Walter,” he wrote. “Stop over in Washington on your trip home and let’s celebrate. I sincerely hope that my dollar is the dollar that did the trick.”

Walter Johnson had left Sol Bloom’s coin at home, opting instead to toss a Roosevelt dollar inscribed with the message, “Walter Johnson threw this dollar across the Rappahannock River, February 22, 1936.” This personalized touch added a unique and memorable aspect to the event.

“The wind was against me and I didn’t know whether I could make it or not,” Johnson said afterward. “… I’m glad I could prove George did it, especially after Sol Bloom made a campaign issue out of it.”

The New York Times reported that only about 200 people remained for the dedication of the cherry trees after witnessing Walter Johnson’s toss in Fredericksburg.

Folliard, who covered Johnson’s toss for The Post, later went on to cover significant events such as the White House and World War II for the newspaper, ultimately winning a Pulitzer Prize in 1947.

Years later, as documented by Shirley Povich, Folliard told a crowd at the National Press Club that witnessing Johnson’s feat was among the highlights of his career, showcasing the lasting impact of the event.

“As man and boy, that was my biggest thrill,” Folliard said. “You see, I was the fellow who held Walter Johnson’s coat.”