Japanese film has been one of global cinema’s top standards since Thomas Edison introduced the kinetoscope to the Japanese in 1896. Japanese filmmaking has always been able to strike the ideal balance between light and shade, the ideal mix of whimsy and solemnity to examine otherwise inaccessible areas of the human condition.

This is due to the country’s rich, distinctive aesthetic tradition and brutal feudal history. The Yakuza movie is one of the most well-known film genres to have originated in Japan. The Yakuza is basically the Japanese Mafia, distinguished by their vicious behavior and rigorous adherence to their individual standards of conduct.

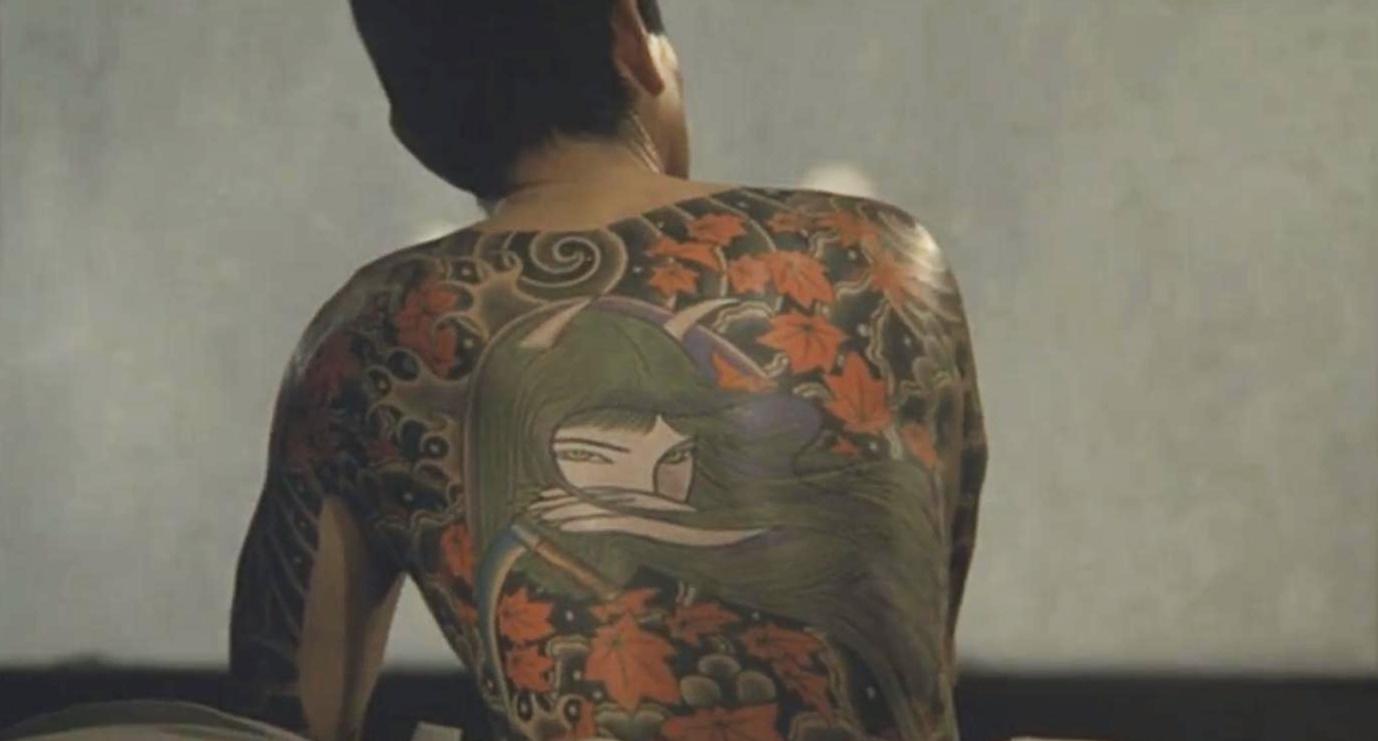

The films of this genre frequently feature significant portions of their founded ritual practices, such as yubitsume (the customary act of cutting off a finger as a way of sincere apology) and full body tattooing (or irezumi), and they frequently explore themes of extreme loyalty, respect, family, and adaptation to shifting social landscapes.

Japanese movies before World War II typically focused on the adventures of bakuto, roving gamblers who predated and later evolved into the current Yakuza. Famous national legends were presented in these movies as empathetic Robin Hood-like figures who were compelled to live a lonely outlaw existence.

Yakuza films did not acquire the moral ambiguity and complexity that the bakuto stories lacked until the post-war works of Japan’s most-known filmmakers, such as Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu. Here is the list of 30 gangster movies that you should definitely have a look at if you are a fan of this genre, this list may surprise you.

30. Ryuji (1983)

Ryuji is the only classic Yakuza movie that has been made since the 1970s, according to Kinji Fukasaku, the famed director of Battles Without Honour and Humanity, which is widely regarded as the best Yakuza movie ever.

Additionally, for a good reason, author/star Shoji Kaneko Toru Kawashima subverts the traditions of the genre by providing a low-budget depiction of the contemporary Yakuza in which tradition and ceremony are reduced to running gags. The realistic method used in Ryuji served as a model for Takeshi Kitano and Takashi Miike’s more recent masterpieces.

Ryuji, a high-ranking Yakuza member, is let out of jail. Despite being feared and revered inside his group, he wants to leave the Yakuza life and take care of his young family. The allure of reuniting with his old group, though, might be too great to resist given his rising obligations and the enticement of cheap cash just around the corner.

Less than a month after the movie’s debut, Kaneko tragically went away following a fight with cancer, but his sensitive, nuanced portrayal of the damaged title character made sure that his legacy would be remembered fondly.

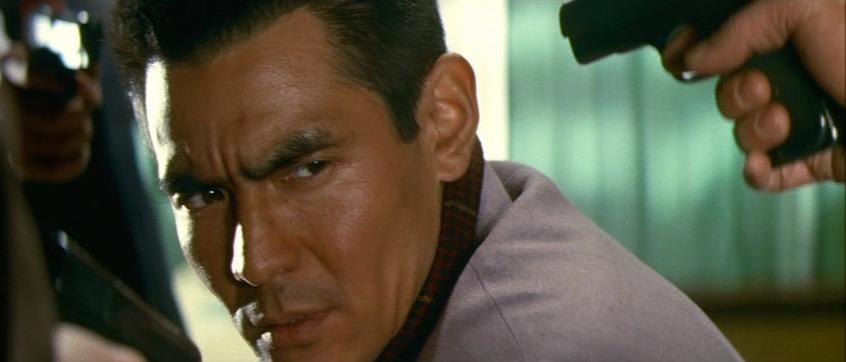

29. Branded to Kill (1967)

The Nikkatsu film company produced a number of Yakuza movies in the 1950s and 1960s that heavily referenced American gangster and noir films. The Ninkyo Eiga (chivalry films) subgenre, which portrayed the Yakuza as heroic outlaws much in the way of pre-war filmmaking, was the most well-liked among the general population during this time.

Seijun Suzuki’s 1967 film Branded to Kill, which Nikkatsu president Kyusaku Hori deemed “incomprehensible,” is now regarded as an influential masterpiece and has had a significant influence on the works of directors like John Woo and Quentin Tarantino. However, Nikkatsu was mainly remembered for the irreverent works of director Seijun Suzuki.

The third-ranked contract killer in the Japanese underworld is Goro Hanada, a Yakuza assassin who enjoys the smell of boiled rice. He is forced into a chaotic struggle for survival and his sanity after failing to complete a challenging contract that a mystery woman promised him. This struggle ends in a confrontation with the mysterious Number One. The Japanese cinema business banned Suzuki after this project, and he didn’t work for another 10 years. Despite this, Suzuki’s cult fame only grew.

28. Sonatine (1993)

Surprisingly, filmmaker Takeshi Kitano started out as a humorist, though you wouldn’t know it from the intensity he gives to this movie as the writer, director, and main actor. When Kinji Fukasaku, a fellow Yakuza film expert, became ill in 1989 while working on the set of Violent Cop, Kitano earned his start as a director.

In the years that followed, Kitano refined his technique to the point where he could create a fluid work that was as captivating and graceful as Sonatine. Murakawa, a Yakuza enforcer, is skeptical when his group is sent to Okinawa to arbitrate a minor gang conflict.

When his group is ambushed, and several people are killed, his worries are validated. Murakawa seeks cover in a beach house with the survivors as he prepares his retaliation. Sonatine demonstrates an author at the height of his abilities, balancing deeply poetic passages with horrifically violent ones.

27. Hana-Bi (1997)

Takeshi Kitano established himself as the preeminent Japanese filmmaker now working on the international scene with this movie and Sonatine. Even if this claim were debatable, few would contest the critical acclaim Kitano’s creative output has received on a global scale, including the renowned Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for Hana-Bi.

The movie’s title translates to “fireworks” in Japanese, but Kitano hyphenated it to signify the dual duality of his lead character, Nishi. Hana, which means “flower,” is a symbol of life, but bi, which means “fire” and is a representation of gunshots, is a symbol of death.

Kitano portrays Nishi, a violent and corrupt police detective. With his wife battling cancer, his Yakuza debts mounting, and his partner now restricted to a wheelchair following a deadly gunfight, Nishi makes a sad decision.

The entire movie is anchored by Kitano’s controlled performance; he effortlessly switches between great joy and extreme violence, yet it is a tribute to his directorial that none of these gory scenes feel forced and always fit the character.

26. The Yakuza (1974)

The Yakuza is the ideal place to start for someone unfamiliar with Japanese cinema because it is the only movie on this list that was produced in the west. It takes a thorough yet obviously western approach to the mysterious world and practices of the Yakuza, using action and plot when a Japanese director would be content to exclude them.

The Yakuza, directed by the dependable Sydney Pollack from a screenplay by the legendary Robert Towne and Paul Schrader (with his brother Leonard), deftly balances the opposing ideologies of the west and the east, culminating in a chaotic clash in the style of Paul Schrader.

Harry Kilmer, played by Robert Mitchum, is a private eye who has a strong connection to Japan because, when serving as a marine stationed there after World War II, he fell in love with Eiko and was forced to leave at her brother’s request. Nearly 30 years later, he is charged with assisting a close friend whose daughter the Yakuza has abducted.

The relationship between Mitchum and Eiko’s brother, played by Yakuza movie staple Ken Takakura, gives the movie its actual strength and emotional center. Mitchum’s presence alone is enough to carry the movie.

25. Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973)

With this instant classic, frequently referred to as the “Japanese Godfather,” Kinji Fukasaku cemented his position as the leading Yakuza film director of his generation. It is regarded as one of the very first current Yakuza movies and was shot in a documentary-like manner. Although many had portrayed the Yakuza in its modern incarnation, few had the ambition to have unredeemable antiheroes as their main characters.

Additionally, it stands apart from other prominent Yakuza movies of the era due to its violence and fast pace. It remains near the top of many “best of” lists, including fifth on the famous Japanese film publication Kinema Junpo’s best all-time film list. It is based on the memoirs of genuine Yakuza member Kz Min.

The epic movie, which spans ten years, centers on the exploits of young Yakuza criminal Shozo Hirono. Hirono, who is trying to create a reputation for himself within the underworld, observes the changing of the area Yakuza leaders and ruling families in Hiroshima after the war. The movie was the first in a massively popular, five-part series that ultimately altered Japanese filmmaking forever.

24. Ichi the Killer (2001)

One of Japan’s most productive filmmakers now active in Japan is Takashi Miike. He was accredited with directing 15 pictures in the years 2001 and 2002 alone, demonstrating his tremendous levels of productivity. His variety is nearly unsurpassed, spanning from slick crime fiction to teen dramas and dark humor.

But among his films, his translation of the manga serial Ichi the Killer stands out as being highly divisive. Due to the intense sexual violence and gore, the movie underwent significant editing and was outright banned in some nations. Despite this, the stylized violence and frantic direction made it a cult classic with enormous influence. Kakihara will do all it takes to get even with those responsible for the murder of his boss.

He discovers a plot to rid the city of its Yakuza as he cuts his way through the underbelly of Shinjuku, sparking a gang war in the process. The homicidal outbursts of the psychotic killer known only as Ichi are the driving force behind this plan.

As the bodies pile up and the blood pours, Kakihara and Ichi get closer to their final encounter, from which neither will survive unscathed. The picture goes forward at an incredible rate thanks to Tadanobu Asano’s severe performance as the sadomasochistic (and potentially demonic) Kakihara, which is wonderfully balanced by Nao Omori’s twitchy craziness as Ichi.

23. Graveyard of Honor (1975)

According to assistant director Kenichi Oguri, realism is the secret to any of Kinji Fukasaku’s excellent Yakuza movies, and he frequently chose players who would give their all in physical sequences. Graveyard of Honour may be the pinnacle of this philosophy because it is incredibly honest in its focus on the self-destruction and persisting madness of its lead character.

It is one of the darkest Yakuza flicks because it has one of the most repulsive antiheroes to ever appear in cinema. It is strong and unrelenting in its gloom. This movie depicts the, especially in the post period of Rikiko Ishikawa’s rule, and is based on the real story of the former Yakuza chief.

It focuses on the consequences of his violent behavior and the punishments he receives from his own gang, as his drug use and contempt for both his allies and foes put his tenuous hold on power in jeopardy. A well-known version was helmed by Takashi Miike in 2002, who added more bloodshed and brutality in his own distinctive manner.

22. Drunken Angel (1948)

Film historians regard Akira Kurosawa’s seminal work as the director’s first important piece of work, as well as the first to portray the post-World War II Yakuza as they are known today. Kurosawa depicted a young criminal negotiating the terrain of an occupied Japan, departing from the typical pre-war representations of the bakuto.

As much social critique as the US censors would permit smuggled in by Kurosawa, the outcome is similar to the contemporaneous Italian neorealist cinema trend. Although the issues covered in the movie aren’t typical of the genre, Kurosawa’s method and Toshiro Mifune’s electrifying performance would pave the way for the 60 years of Yakuza movies that followed.

When the clan leader is locked up, Matsunaga, a low-level Yakuza criminal, starts drinking and having affairs. He is cured by a native alcoholic doctor after a fight with a competing gang, and the two develop an odd bond. When his boss is let out of jail, Matsunaga discovers that his standing in the gang is less secure than he had believed. Mifune makes an appearance in the first of Kurosawa’s sixteen films with him, which also features prominent roles in Rashomon and Seven Samurai.

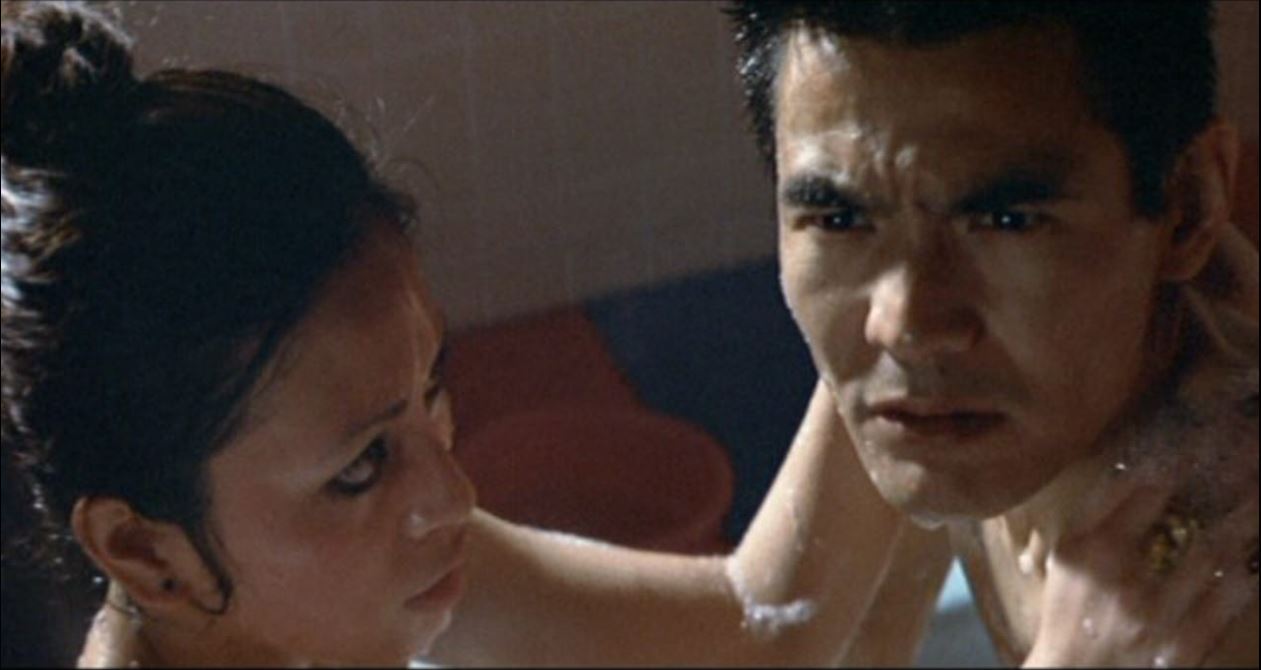

21. Another Lonely Hitman (1995)

Without sacrificing the intensity and brutality of a typical Yakuza movie, Mochizuki Rokuro’s character study of a guy who is having a difficult time accepting change is profoundly compelling. With influences like Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, Another Lonely Hitman can be understood as bridging the gap between the grim, serious Yakuza flicks of the 1970s and the cinema of the twenty-first century.

But it stands out from the crowd as a movie of great worth because of an emotional resonance not typically connected with the genre. A vintage Yakuza hitman is horrified to discover that his gang is now peddling narcotics and that the code of behavior he used to follow has been abandoned after serving a ten-year prison sentence.

Being a recovering addict, he develops sympathy for a local call girl. However, when he steps in to protect her from an assault by a member of a rival group, he finds himself the target of two different gangs. Ishibashi Rio gives a nuanced portrayal that earned him Best Actor at the Japan Film Professional Awards by giving the lonely hitman a lot of sympathy.

20. Velvet Hustler (1967)

In Japan, director Toshio Masuda is regarded as a dependable box office victor; over his 50 years of production, 16 of his films have placed in the top ten for box office take. However, it is his work with Nikkatsu in the 1960s that has endured the greatest and, along with Seijun Suzuki, a contemporary, defined a time in cinematic history.

The song Velvet Hustler (or Like a Shooting Star), with its French New Wave influences and brilliant colors, is the best example of his style at this time. It is among Nikkatsu’s best, not to mention Masuda’s finest moment, and is rife with action and a playful self-awareness.

Young Yakuza hitman Goro keeps quiet after finishing a lucrative job in Tokyo. Although he is able to remain silent and have an active life as desired, he finally becomes a suspect in the killing of a young woman. Another hitman is pursuing him at the same time in vengeance for the assignment he completed in Tokyo. The zany brilliance Joe Shishido has honed through his multiple partnerships with Seijun Suzuki comes through as Goro.

19. Abashiri Prison (1965)

Although Teruo Ishii’s 1965 film was the first authentic Yakuza movie, Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel is still regarded as the first true Yakuza movie. It established Ishii and star Ken Takakura as household celebrities, and Ishii went on to direct twelve sequels as a result of the movie’s success.

A notorious prison in Hokkaido is called Abashiri Prison. As he waits for the final six months of his sentence to pass, Shinichi Tachibana is a model prisoner who tries to keep to himself. When veteran Yakuza member Gonda breaks free while handcuffed to him, Tachibana is forced to flee. In an effort to avoid the law, the two try to form a tense alliance. As Tachibana and Gonda, Takakura and Koji Nanbara complement one another beautifully.

18. Youth of the Beast (1963)

This chaotic journey through the underworld of Tokyo is once again directed by Seijun Suzuki, who is known for his anarchic style. Here, his superb use of color, furious jazz music, and elegantly dressed killers are all on display, cementing him as a cult favorite.

Suzuki’s usual ridiculousness is added in scenes such as when a man has his hair set on fire with an aerosol can and a lighter, giving his Yakuza B-movie canon another potent entry. Joe Shishido, a well-known Yakuza actor, portrays a teenage criminal who is recruited by the local Yakuza because of his unstable and aggressive behavior.

Once he joins, he begins making deals with other gangs to play them against one another, and it quickly becomes clear that he has other goals. Shishido is a regular character in Suzuki, and in this movie, he is at the height of his abilities. His aggressive style and easy coolness perfectly capture Suzuki’s vibrant vision of Tokyo.

17. Street Mobster (1972)

Another Kinji Fukasaku movie on this list simply serves to highlight his enormous influence and prodigious talent in the Yakuza movie genre. His meticulous attention to detail and refusal to shun social deterioration and brutality set the tone for the harsh tone of 1970s Yakuza cinema.

His renowned epic Battles Without Honor and Humanity was made possible by the ideas and scope of this picture. When a Yakuza member is freed from jail, he discovers that his former gang is in ruins and that the political climate of the underground has drastically changed.

He must lead the remaining members of the gang to claim a new region in order to reposition them as a formidable gang, despite his relative lack of expertise with the new ways, unbridled aggression, and contempt for authority. Because he had many Yakuza buddies, Bunta Sugawara not only gave a terrific performance as the lead but also gave Fukasaku many script recommendations.

16. Minbo, a.k.a. The Gentle Art of Japanese Extortion (1992)

Juzo Itami, a satirist, best known for his screwball ramen western Tampopo, was a master at using humor to subtly highlight the various flaws in Japanese culture. Itami was especially cruel in the comedy Minbo, which follows a brave lawyer (Nobuko Miyamoto, Itami’s wife, and frequent collaborator) as she aids a posh hotel in fending off a swarm of Yakuza who are trying to extract money from it through fabricated civil issues.

The gangsters here lack any of the honor or cool frequently associated with them in popular culture and are instead portrayed as little more than craven, thuggish thugs seeking to con honest citizens, which is a mirror of the anti-yakuza onslaught of its time.

In this regard, Minbo makes a particularly sharp observation on the frequently conflict-averse attitude of contemporary Japan while offering possibly the least sympathetic portrayal of Japanese organized crime ever put to film. It’s important to note that this movie and Tokyo Vice have an intriguing, though the tragic, link.

After Minbo was made available in Japan, members of the Goto-gumi, a branch of one of the biggest yakuza groups in the nation, planned an assault on Itami and brutally beat and slashed him. The yakuza organization that the actual Jake Adelstein told about encountering in Tokyo Vice is this one (the book). Adelstein supposedly discovered the real reason for the filmmaker’s strange death, which was a murder that was misdiagnosed as a suicide.

15. Brother (2000)

Takeshi Kitano produced numerous movies on the Yakuza, including coming-of-age tales (Kids Return), road movies (Kikujiro), and even a whole movie about a group of grandfather yakuza out and about (Ryuzo and the Seven Henchman). Brother, the only movie Kitano made in America, is arguably one of his underrated works.

He plays Yamamoto, a yakuza who is compelled to leave for Los Angeles after his clan is broken up, in the movie. When he meets up with Ken, his younger half-brother, he discovers that he, too, is involved in gang activity. In order to dominate Los Angeles or perish trying, Yamamoto organizes a new yakuza clan with his half-brother and his Black pals rather than giving up and retiring.

Brother, a movie about Yakuza entering America, draws an interesting comparison to Tokyo Vice, a television program about an American entering the Yakuza. Similar to this, Yamamoto’s foreignness is highlighted by the fact that at the beginning of the movie, he is completely lost in translation. But as the story progresses, he strengthens his bonds with his LA crew, particularly Denny, played by Omar Epps. A random heroin dealer from Los Angeles is forced to commit yubitsume in another scene.

14. Why Don’t You Play in Hell? (2013)

A yakuza film about creating a yakuza film is called Why Don’t You Play in Hell. An absurdist criminal odyssey with a jumble of seemingly unrelated parallel stories that eventually collide spectacularly, including a conflict between two warring yakuza clans.

The exploits of the Fu#k Bombers, a group of overzealous but ineffective guerrilla filmmakers, and a love story that included the would-be starlet daughter of one clan’s oyabun. A grandiose fever pitch is reached in the story’s blood-soaked and cocaine-dusted final act, despite the fact that it takes place over the period of ten years and, well, sounds fairly filthy.

13. The Blood of Wolves (2018)

1988 saw Hiroshima. Shuichi Hioka, a young, university-educated junior investigator, is partnered with Shogo Ogami, a crude and unconventional senior detective. The two cops look into the death of a bookkeeper with connections to the Yakuza, but as they dig more into the case, Hioka becomes less certain that he can believe Ogami, who not only behaves and dresses like a thug but is also reputed to be working for the mob himself.

Hiroshima was in 1988. Shogo Ogami, a gruff and unorthodox senior detective, is partnered with Shuichi Hioka, a young junior investigator with a university education. The two police officers investigate the death of a bookkeeper who had ties to the Yakuza, but as they learn more about the case, Hioka starts to question if he can trust Ogami, who not only acts and looks like a thug but is also rumored to be employed by the gang.

12. First Love (2019)

After learning that he has a brain tumor, silent, lonely boxer Leo explores the streets of Tokyo in disbelief. Indentured to the mob as a call girl, Monica uses drugs to block off horrific memories of her abusive father.

The two come into contact in one of cinema’s strangest on-screen romances when Leo instinctively punches out a cop who is trying to frame Monica for stealing a sizable shipment of drugs. This puts the two in the middle of a conflict between the Chinese and Japanese triads, who are both after the couple’s blood.

Despite having produced more than 100 feature films in the roughly 30 years since his debut, Takashi Miike is perhaps most recognized abroad for his use of gruesome visuals and gratuitous gore. His most notorious films, including Ichi the Killer and Audition, reach such a pinnacle of crazed violence that Eli Roth resembles Ken Burns in them.

So it’s all the more amazing that Miike manages to mix First Love’s exhilarating violence, hilarious comedy, and unexpected sweetness so well. It reminds me of Quentin Tarantino’s True Romance. It’s a romantic comedy of errors between young misfits involved in a criminal situation, supported by a cast of great characters, most notably a hyperconfident but ungraceful yakuza cleaner whose desire for power starts the whole messy fiasco and provides many of the movie’s biggest laughs.

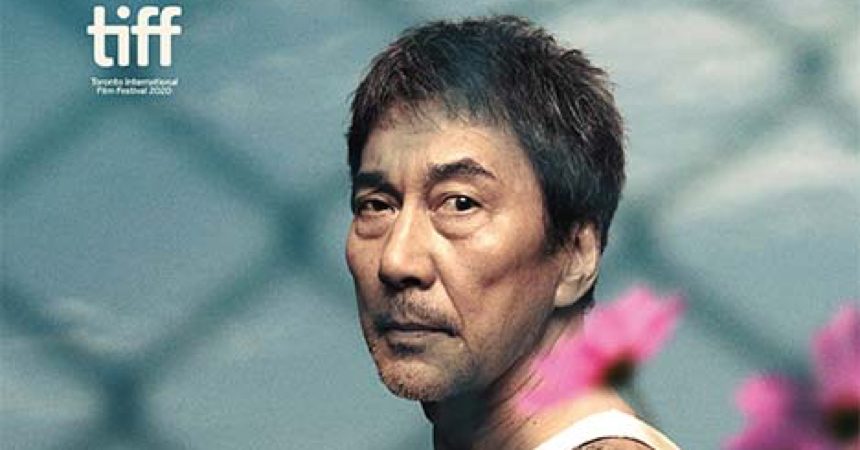

11. Under the Open Sky (2020)

Former yakuza Mikami is keen to walk the narrow path after serving a lengthy jail sentence, but he finds it difficult to integrate into a community that may not want him. Although he is sincere and diligent, his impulsiveness and refusal to compromise his convictions scare and repel many around him, including the TV producer he hopes, would bring him in touch with his long-lost mother.

In the end, the decision is between Mikami continuing a futile fight and choosing the simple route back to a life of crime. Miwa Nishikawa, the film’s director and a student of Shoplifters director Hirokazu Kore-eda, is particularly interested in exploring how anti-yakuza laws hinder former members’ recovery and prevent their reintegration into society. It’s a subtle, moving drama about adjusting to and surviving in a world where everything is stacked against you.

10. Alice In Borderland (2020)

When Alice in Borderland debuted, it quickly rose to the top of the charts in Hong Kong, reviving the image of Japanese dramas. The manga-based drama is set in a futuristic Tokyo and centered on aimless gamer Ryohei Arisu (Kento Yamazaki), who discovers the once-bustling city has been abandoned after meeting with his buddies in Shibuya station.

A voice directs him to a game they have to play, but it’s not just any game; they have to play it to survive. Despite its grim survivalist setting, the drama is packed with thrills and excitement, which may be exactly what we all crave when we’re alone. Fans loved it so much that it was renewed for a second season, and everyone is anticipating the release of the new season in December.

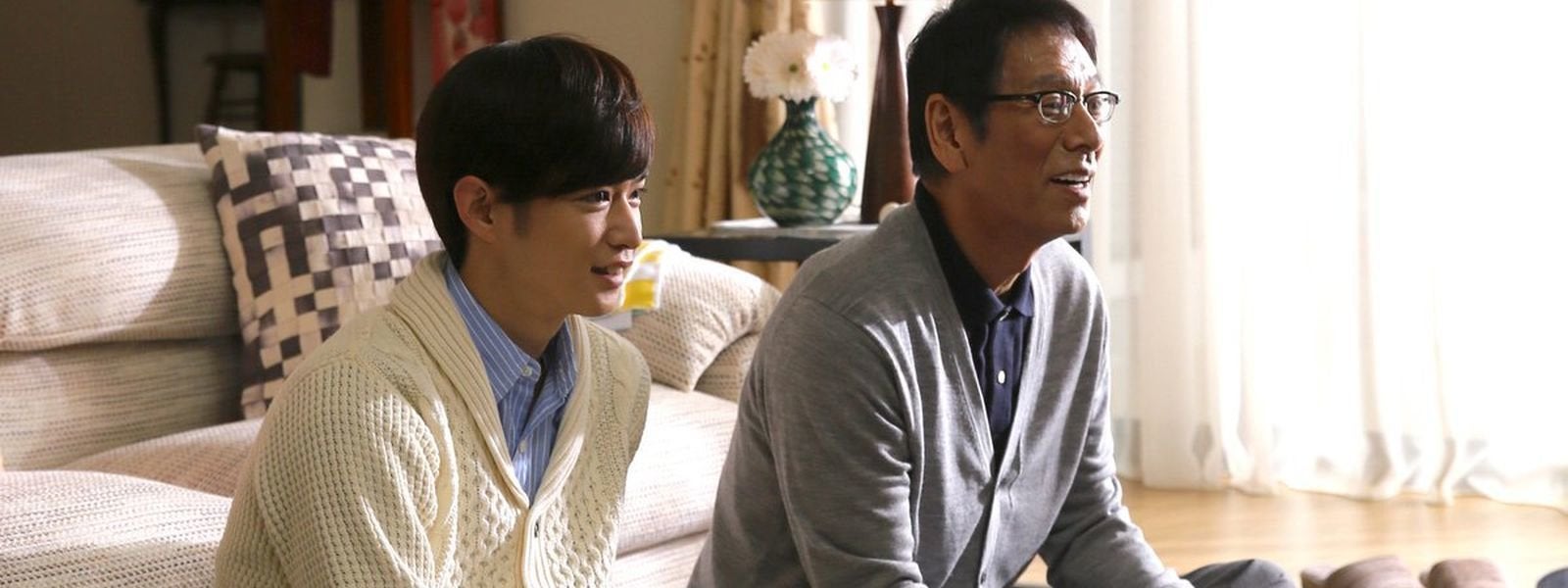

9. Final Fantasy XIV: Dad of Light (2017)

When Akio’s diligent father, Hakutaro, abruptly decides to leave his office job one day without giving any notice, he is confused. For the majority of Akio’s existence, Hakutaro was typically concerned with work. Therefore the two rarely had much time to interact.

Akio reintroduces his father to Final Fantasy, a video game the two formerly bonded over when Akio was just a small boy, in an effort to come to know and understand him better. Hakutaro notices that his interest in the game is growing now that his job isn’t taking up all of his leisure time. Akio has been playing the game covertly under an alias in an effort to convince his father to confide in him.

This shockingly underappreciated treasure, which is based on a true story, is broken up into an eight-part miniseries. You’ll want to grab some Kleenex and think about buying the most recent Final Fantasy, which stars Yudai Chiba as Akio and Ren Osugi as Hakutaro.

8. Ride or Die (2021)

Rei, a young woman from a rich family, receives a surprising call one day from her old high school buddy Nanae. Rei is excited to see Nanae even though it has been ten years since they last spoke because they attended the same high school together, and she used to harbor romantic sentiments for her.

Rei learns that Nanae is an abused wife who is locked in an abusive marriage when she is reunited with her buddy. The two friends gradually develop a new level of familiarity until Nanae asks Rei whether she would assist her in killing her husband.

In this riveting psychological drama presented as an LGBT romance, Kiko Mizuhara (Norwegian Wood, Attack on Titan) and co-star Honami Sato (‘The Cornered Mouse Dreams of Cheese’) make a comeback to full-length films. Ryuichi Hiroki, who also directed the 2014 movie “Kabukicho Love Hotel,” adapted the story from Ching Nakamura’s manga “Gunjo.”

7. Age of Samurai: Battle for Japan (2019)

Oda Nobunaga takes over as the Oda clan’s new leader after his father passes away, and he quickly begins to seize power in central Japan. However, Nobunaga is not the only daimyo who aspires to unify the country under his absolute reign.

The following decades of 16th-century Japan become a crucial period in history for the nation and its rulers due to political intrigue and bloody samurai warfare. The actual sequence of events is dramatic enough as it is; this specific period in history doesn’t need to be depicted as a period drama to be stunning, action-packed, and full of high stakes.

This documentary series tells the story of the end of the Warring States era in Japan through historical reconstructions of key moments involving historical figures, including Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Re-enactments involve well-known performers like Masayoshi Haneda (‘West World,’ ‘The Last Samurai’), Hideaki Ito (‘Memoirs of a Murderer’), and others, and commentary is provided both in English and Japanese.

6. Demon (1985)

The director of the final New Abashiri Prison episode, Yasuo Furuhata, seems to be drawn to locations covered in snow. A former criminal who retires to a small seaside village in the dead of winter to start over as a fisherman with his family is a self-referential character in this movie, which features the star of the original series. Soon after, a heroin-dependent mobster (played by Takeshi Kitano), who is tempting him back to his old habits from his past, returns to haunt him.

Furuhata seems to be drawing a contrast between the cruel, crude, and avaricious new breed and the traditional death-and-duty character of the pre-1970s gangster that Takakura had made his stock in trade in this rather poignant, character-driven piece created during a slump in the popularity of the yakuza genre. Kitano, Japan’s most well-known comedian and media figure, makes one of his early cinematic appearances here. The latter would later be popularly described by Kitano.

5. The ‘Black Society’ trilogy (1995-99)

It’s hard to know where to start with the yakuza genre flicks that the incredibly prolific Takashi Miike has directed. This loosely connected “Black Society” (kuroshakai) triptych was started soon after he left the realm of straight-to-video V-Cinema and before he achieved international success with Audition (2000).

It is regarded as one of his best works. Each of the titles makes insightful remarks about the Asian racial minorities in Japan, which would appear in a large portion of Miike’s body of work. The first pits a police investigator of a mixed race against a mobster from Taiwan, and the second is about a Japanese gangster who has been exiled to Taiwan.

Although there is much more going on underneath the theatrical on-screen onslaught, they are all characterized by Miike’s quick cuts, highly formed and inventive mise en scene, and hyperbolic attitude to on-screen violence.

4. Midnight Dinner (2009)

Since travel is now postponed, Midnight Diner: Tokyo Stories is a fantastic way to satisfy your craving for Japanese food. The story revolves around Meshiya, a late-night eatery in Shinjuku run by the mysterious Master, a chef. In each episode, a different customer tells their entire life story to the Master, who responds by providing support and advice.

The meal frequently represents the character’s favorite and is somehow related to the story. The TV show is well-liked both in and outside of Japan. All of us are in need of the kind of reassuring tales and food that may be found in inspiring food stories. The Master’s advice may be vital to a particular character, but viewers might also take something away from it and identify with it.

3. Giri/Haji (2019)

Although this show is actually made in the United Kingdom, I know you all wished for a show about the Yakuza, the well-known Japanese Mafia. But don’t worry, there are several situations when they speak Japanese, and a portion of the series was filmed in Tokyo. In Japanese, Giri/haji signifies “Duty/Shame.”

Detective Kenzo Mori travels from Tokyo to London at the start of the series in search of his brother Yuto, who inexplicably vanished and was thought to have died. Yuto was a yakuza member who was charged with killing a yakuza boss’s nephew before going missing. He encountered the violent London underworld while looking for his brother Kenzo.

2. Samurai Gourmet (2017)

Samurai Gourmet, a simple-to-watch series with only 12 chapters lasting 20 minutes each and based on the comic Nobushi no Gourmet by Masayuki Kasumi, is another Japanese series that has seen considerable success outside.

Samurai Gourmet opens with a circumstance that is quite typical in Japan: Takeshi Kasumi, a salaryman who has spent his entire life working and who is now in his 60s and has just retired, is unsure of what to do with all of his spare time. But eventually, he starts to learn about unfamiliar places in his neighborhood and starts to relish the pleasure of dining.

Additionally, he recalls memories from his youth through eating. Maybe a lot of you will have questions. Okay, but where are the samurai? Actually, Kasumi’s imagined alter ego—the samurai—exists only in her mind.

Due to Kasumi’s shyness and insecurity, she often assumes the guise of a samurai when there is a fight or other stressful situation. This ronin, or samurai without a lord, is the antithesis of Kasumi: haughty and pompous. Somehow, this warrior encourages Kasumi to show greater bravery and resolve.

1. Battle Royale (2000)

Though this movie is not a gangster drama but this dystopian horror film, which is packed with action and gore, is actually regarded as one of the best films of the whole decade, not just in the horror subgenre. It basically invented a new genre and has impacted many other forms of media.

Any scenario in which a number of people are encouraged to kill each other out until only one person is left is now referred to as a “battle royale.” In order to regulate the country’s youth population, the government passes a law in this movie that compels a group of roughly 50 high school students to engage in a match to the death.

Does The Hunger Games seem familiar to you? Okay, so it’s not (this film came first). They are neither strangers nor professionals. These are classmates competing against one another without any prior preparation. As you witness them commit murder in order to survive, it makes you doubt your own values and makes you consider what you would do.